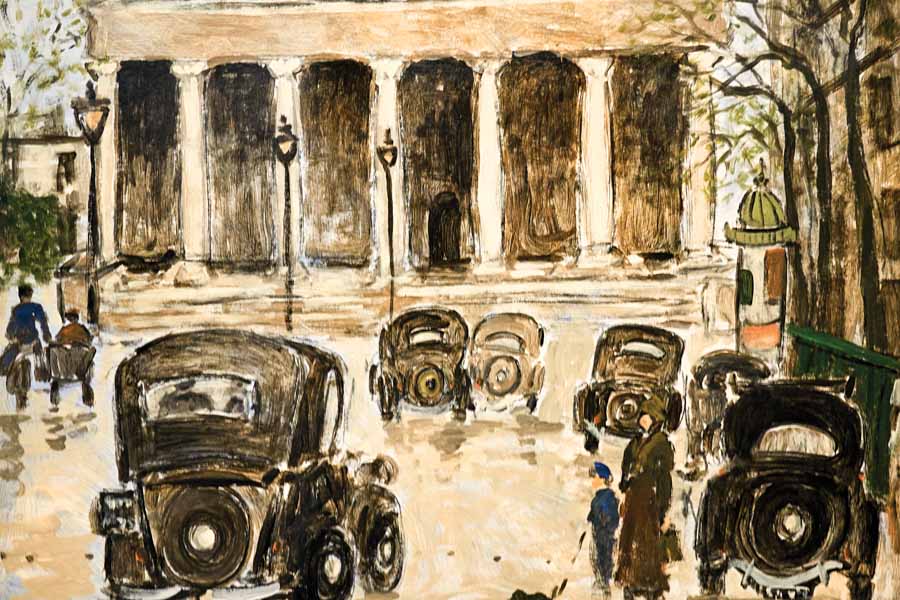

Like all good Frenchmen, Henry St. Clair loved art—of this there was no doubt. A moneyed fellow born 1899 in the Normandy region of France, he ventured south as an art restorer, working for the National Museums of France and eventually bringing his trade to its Parisian epicenter at The Louvre, where he could spend his days with the artists he so admired. But St. Clair had a secret about how he spent his nights, one that wouldn’t out until his death in 1990, when a nephew discovered near 2,000 original paintings, created from 1920 to 1970 and hidden away in a nondescript barn on the property. At first, no one knew what to do with them, but as word spread and St. Clair’s star began to posthumously rise, the bidding wars began—one gallerist found his fortune, another got booted from a Palm Beach convention and the last of the St. Clairs somehow wound up in Sarasota.

“I was just mesmerized,” says collector Diane Kaslow, of the first time she saw St. Clair’s work. She had just moved to Paris on business, didn’t speak the language and took to wandering the galleries, museums and antique shops where the visual language required no translation. A post-impressionist, St. Clair took his cues from the likes of Eugene Boudin, capturing the beaches of Normandy with a similar attraction to idealized scenes of French coastal life, and Raoul Dufy, whose exuberant color palette reflected an early adherence to the short-lived Fauvism movement. He worked on painter’s board instead of canvas, combining thick indicative lines with a thin wash of paint to create an airy and almost transparent effect, like a memory gone ghostly with age. Kaslow called her husband to let him know she was about to buy four paintings on the spot. “Why don’t you just buy one?” he said.

Kaslow conceded, but the specter of St. Clair haunted her. Everywhere she went on the streets of Paris, she began to see his work—and the prices were going up. Two weeks before she returned to the states, at an outdoor show near the Bastille, Kaslow made up her mind. “I can sell these,” she said, and bought six to bring back to a gallery in Nantucket. Four sold in a week, and everyone wanted to know the same thing—“Where can we get more?”

Enter Jean Charles La Porte, the unknown and unkempt gallerist who originally purchased the 2,000 paintings from St. Clair’s nephew, slowly restoring them and introducing them to the market 30 or so at a time, trying to build a name for himself and St. Clair at the same time. “Scruffy,” Kaslow describes him, with crazy hair and an untucked shirt but “punching above his weight class” nonetheless. Striking up a friendship with La Porte, Kaslow became the sole American with inside access to St. Clair’s body of work, alongside a cabal of five Parisian dealers. And every time La Porte would release a new batch, Kaslow would cross the pond to pick up 15 or so to bring back to her Nantucket clientele. 45 sold in the first year, with prices ranging from $3,000 all the way to $20,000. Over the course of six to seven years, all involved enjoyed the fruits of this partnership. Kaslow continued to sell at record numbers, even expanding her focus down south to Florida, where she began to sell St. Clair’s paintings from a mobbed 10x10 booth at the annual Palm Beach Jewelry, Art and Antique Show. La Porte became a bonafide gentleman art dealer, with combed hair, pressed suits and an invitation to the Parisian salons. And St. Clair enjoyed a second life, as the art world at large began to take notice. But nothing gold can stay.

Today, La Porte is dead, and the last of the 2,000 paintings sold off. St. Clair’s ascent has temporarily stalled, as the discovery leaves the honeymoon phase and the lack of scholarship begins to weigh on collectors’ minds, creating a feedback loop difficult to escape, with both scholars and collectors waiting for the other to make the plunge first. Even Kaslow experienced backlash, disinvited from the Palm Beach exhibition after other proprietors complained that her prices were undercutting competition, as the apparent disconnect between St. Clair’s commercial appeal and critical scholarship resulted in high demand for a comparably lower price tag than the rest of the vendors would have liked.

But Palm Beach’s loss is Sarasota’s gain, as the final 23 St. Clairs of Kaslow’s collection have made their way to the walls of Galleria Silecchia on Palm Avenue, having traveled near 4,600 miles and 100 years to get here. And in a town of collectors and art appreciators, perhaps St. Clair has been forgotten for the last time.