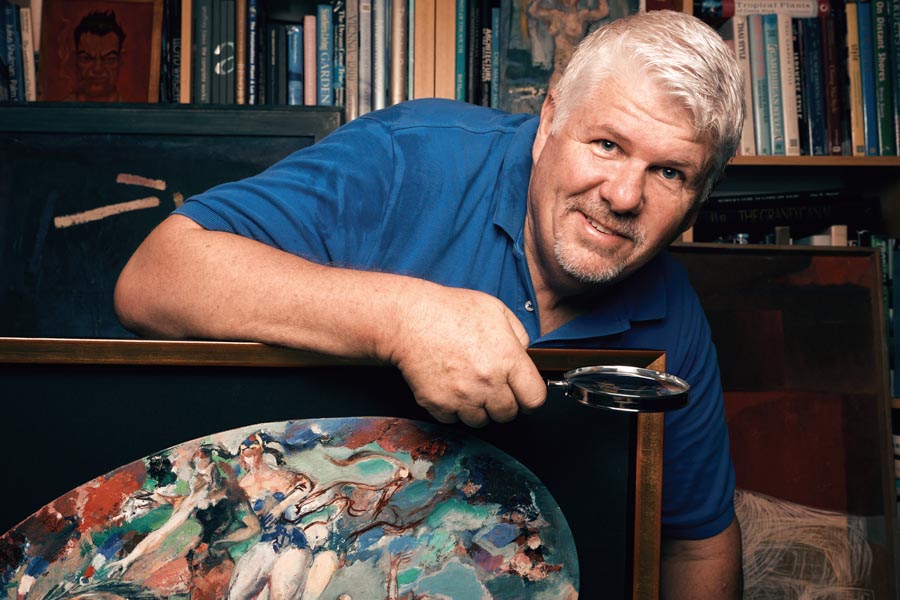

It’s late on a Saturday morning and Eric Bowyer, Sarasota treasure hunter, makes his rounds of the local garage and estate sales, as he does just about every Saturday. “Every weekend you miss,” he says, “you might miss a treasure.” And treasure abounds in these waters. He’s found Renoirs before, unnoticed and underpriced, and countless gems of mid-century modern design, from Eames lounge chairs to bubble lamps by George Nelson. One piece he found for $10 in a neighborhood off I-75, and sold this year in New York for more than 43 grand. But on this day, as the sun nears its peak over north Sarasota, in an apartment complex overlooking Palme Aire Country Club, Bowyer finds the missing piece of a decades-old Sarasota mystery, and steps into a world of art heists and unsolved murder.

SARASOTA TREASURE HUNTER ERIC BOWYER UNCOVERS A MISSING MASTERPIECE IN JON CORBINO’S “PALETTE.” PHOTO BY WYATT KOSTYGAN.

A Mystery Unearthed The painting stood out amidst the knick-knacks and tchotchkes that comprised the rest of the estate sale, Bowyer remembers. Odd and out-of-place, it burst with energy and color alike, a circus-themed fairy tale rendered on a painter’s palette. “You could see the quality right away,” Bowyer says. And something about the signature caught his eye. It seemed familiar. It escaped him. It bugged him. All the seller could say was that, like the rest of the items and the apartment they were in, it belonged to her dear old sister, now deceased. The price tag said $25. Bowyer bundled it with another piece and the old woman gave it to him for $20.

Back at home, Bowyer began his research. “To Eva Lee,” read the inscription on the painting, and the signature attributed it to none other than Jon Corbino—the famous Italian-born American painter of the mid-20th century, whom Life magazine once dubbed the “modern-day Rubens” and whose work sits in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Carnegie Institute and others. He reached out to experts for authentication, including the artist’s daughter, Lee Corbino. The work was genuine, she said, and the title Palette. And in 1991, she said, it was stolen.

Originally created for a New York gallery owner—the aforementioned Eva Lee—Corbino painted the work in the early ‘60s, shortly before his 1964 death here in Sarasota, and it would eventually find its way into the hands of one William Flook, whose widow would donate it to the Fine Arts Society of Sarasota in 1972. For nearly 20 years after that, it would be undisturbed, on display at the Van Wezel Performing Arts Hall, until, one weekend in late November, when it simply disappeared. It’s likely that George Burns himself was onstage at the time of the theft, but unlikely Burns was ever seriously considered as a suspect. But Bowyer worried that he might be.

“She doesn’t know if I stole it, who stole it or whatever,” he thought, and set off to preemptively clear his name. He had to retrace his steps. He had to find that old woman again.

On the Case It had been near a month since the sale, but Bowyer recalled the general area. “Unfortunately,” he says, “those apartments all look alike.” He scanned Google Earth, found a likely suspect as best he could and hopped in the car. He was a couple blocks off. Bowyer prowled the streets looking for something familiar. And while he didn’t see the port-a-potty and construction materials that he parked beside when he got himself into this mess all those weeks ago, the budding detective did spot a conspicuously new roof above a street scarred by recent architectural activity. Perhaps not enough for a warrant, but enough for another round of amateur sleuthing. Throwing the vehicle in park, he set off on foot.

Quickly orienting himself, familiarity crept over Bowyer’s neck as he followed his old footsteps as best he could, his instincts and recollection proving true with every turn and every turn a confirmation. His pace quickens. A left here. A right here. He’s almost there and then he is—back at the front door of an empty apartment once belonged to a dead woman whose name he did not know. Knocking likely a futile gesture, Bowyer returned to his car. But with the apartment number he found a name, a name attached to an obituary without further leads. Another dead end.

A month later, Bowyer would be driving by the neighborhood when a sign advertising an estate sale would catch his eye. It wouldn’t be, he would think. It couldn’t be, he would say. But he would turn his car anyway, following the signs to that same apartment door. But this time the door would be open.

The Plot Thickens Entering the apartment, Bowyer recognized items for sale. He recognized the old woman selling them. She recognized him, and remembered the “pretty” piece he’d purchased when last they met. But she couldn’t (wouldn’t?) tell him where it was from or how her sister came to have it in her possession. Bowyer played it cool, not yet tipping his hand, pushing for answers without raising suspicion. The woman called a younger man over, identifying him as her nephew and son of the deceased. Now outnumbered, Bowyer asked his questions again and the son paused for a moment. His mother had that painting for a long time, he said. “She was storing it for some fellow,” he said. She never hung it and he never came back for it. None of this seemed odd to them.

Satisfied of their innocence in the matter, Bowyer filled the pair in on what he knew of the painting’s less-than-legal path to their relative’s keeping. “Oh my god, my sister’s a thief!” the woman exclaimed, before collecting herself and turning to Bowyer. “Please don’t tell anybody!” But the son had more to say. He remembered the man, who would occasionally bring items to his mother’s house, saying they had come from his own mother’s house up in Venice, and ask her to hold on to them. He couldn’t say why the man had never returned for this one, but he did remember the man’s name.

A quick bit of research revealed that the man lived in the Jefferson Center towers, right across the street from the Van Wezel. And he had been murdered years before. “So obviously he didn’t come back and get his stuff,” says Bowyer. The crime was never solved, but Bowyer looked at the police reports anyways. The reports from the theft were gone, ruined in a flood years back. Still, Bowyer was satisfied that the man “probably was the culprit,” or at least cut a better suspect than he. Having exonerated himself and the dearly departed sister, he contacted the Fine Arts Society of Sarasota.

A Treasure Restored They came by Bowyer’s office in the Rosemary District, a pair of representatives from the Fine Arts Society. They went downstairs to enjoy a lunch at Lolita Tartine, and Bowyer told his story. “What do you want?” they asked. “Nothing,” said Bowyer. “I just want to make sure it gets back on display at the Van Wezel.” They thanked him, paid for lunch and took the painting. Then they sat on the news for nearly two years, sorting out the fine print of the painting’s return and finally unveiling it at the organization’s 50th anniversary earlier this year. 150 people attended, excited to see what some refer to as the most popular piece of the Fine Art Society’s collection. And while a free lunch may not be the biggest payday, it’s worth more to Bowyer than any piece of stolen art ever could. “Stolen art doesn’t have value,” he says, “because it’s been taken away from the public.”