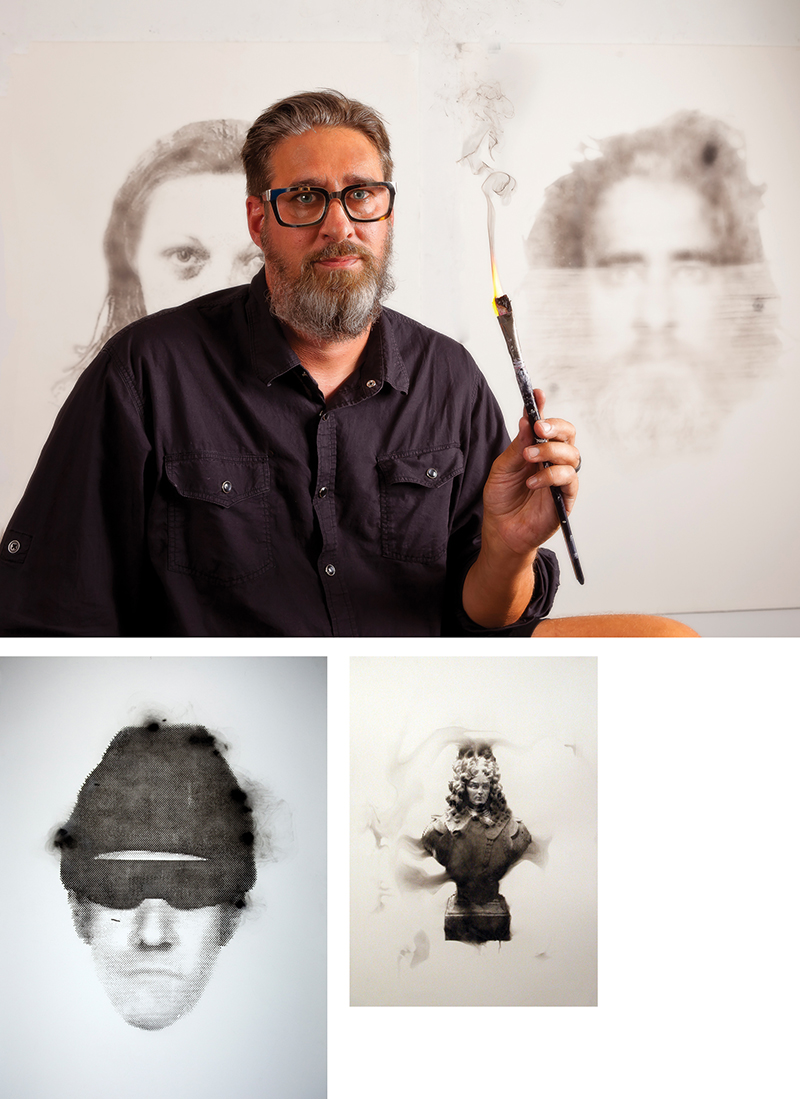

Arthur C. Clarke claimed that any technology sufficiently advanced would appear as magic to the uninitiated and uninformed. Looking over the home studio of Rob Tarbell, artist by trade but more of a modern day alchemist at heart, one wonders if the same could be said of art. Here, in an unassuming garage in the suburbs of Sarasota, is the man who paints with smoke. There’s nothing scary or overtly mystical about Tarbell, who is tall and soft-spoken with a well-groomed beard and gleaming metal-rimmed glasses. More than anything else he exudes an air of imminent excitement, of exuberance bubbling through composure. Almost like a scientist.

“I’ve always been interested in materials and had a material-driven practice,” he says, finding himself drawn to rare media and offbeat combinations, such as stuffed animals and ceramics, through his career. In the artist’s hands, the familiar teddy bear is transformed. Submerged and saturated in porcelain slip, Tarbell poses and then fires the soggy and dripping mass in the kiln. The porcelain hardens and the soft flammable insides burn away, leaving a desiccated and spiny husk like white bone or the shed skin of something monstrous. “It’s getting rid of something to get something,” Tarbell says. A piece from the same series, a formerly fluffy duck with its head half torn off, greets visitors in the front hall.

Tarbell left the kiln in Virginia when he moved to Sarasota two years ago, and in its place constructed his own “smoke room” in the garage—a small and simple wooden box the size of a cramped cell. The first rule behind painting with smoke, Tarbell discovered, is controlling the airflow. “Any breeze makes it difficult,” he says. Clad in coveralls and a gas mask, Tarbell can lock himself in the room for hours, wrestling the smoke into submission and emerging with portraits and scenes simultaneously detailed and vaporous, solid and ephemeral.

The idea began percolating in Tarbell’s brain with the re-reveal of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, freshly restored and cleaned during the 1980s. “My whole college education was the dirty pictures [of the Sistine Chapel],” says Tarbell. “It was brown, very muted, and then they cleaned it and it was just incredibly bright.” With the removal of centuries of grime from oil lamps and smoke, something sparked in Tarbell. “Accumulation will create a mark,” he says.

Two events brought the idea closer to home and closer to realization. Going through a divorce, Tarbell received a book from a friend about moving on and it recommended the traditional ex-fueled bonfire. Setting the artifacts ablaze, he watched the smoke carry the memories away, a life’s accumulation lifted in a pillar of breathy soot. Then, after a night out with a hard-drinking, heavy-smoking friend in Richmond, Virginia, Tarbell attempted to capture the man’s likeness in his vices: liquor and cigarettes. “I failed miserably,” says Tarbell, and the portrait came out a muddled mess. The liquor proved an inconstant dye but the smoke showed promise, even if difficult to control from a cigarette. Reassessing his materials, Tarbell set fire to an old credit card next and watched the gouts of thick black smoke curl in front of him. “It was beautiful, intense smoke,” says Tarbell. “This is what I was trying to get to.”

Collecting unsolicited credit cards from the mail and sending out for more, Tarbell began torching them in earnest, catching the smoke on paper strung above and sketching patterns and forms. “It left the accumulation I wanted, but it also created things my hand couldn’t do, that a brush couldn’t do,” says Tarbell. Depending on the concentration of smoke allowed, Tarbell could create wispy and delicate patterns or coal-black splotches, never leaving a single brushstroke. The only question remaining was how to harness such an unpredictable medium. “It became about controlling the conditions,” says Tarbell. “It was fascinating. I lost all control and had to learn how to control.” Today, Tarbell has this control down to a science. “It’s all about creating conditions,” he says, standing in front of the smoke room. “It’s encouraging or discouraging the flow of smoke.” Where the smoke is allowed direct and prolonged contact with the paper, he’ll get a deep black; wherever the smoke is entirely disallowed will remain stark white. To this end, a great deal of Tarbell’s process and preparation lies in the creation of a layered road map of cut and paneled paper for the smoke to follow.

Between the canvas and the smoke, Tarbell secures a carefully arranged series of barriers and gateways in the form of paper panels and slits in an effort to guide the smoke along the desired path, forming what he calls “gestures.” For his part, Tarbell controls the duration of exposure, but other than that, the smoke travels according to its nature, pooling where allowed and coloring like charcoal, or seeping and crawling through narrow cuts to leave ghostly trails softer than the lightest watercolor. More complex scenes require more complicated maps, and Tarbell will number the panels, removing them in careful order throughout the process.

To catch the smoke, Tarbell attaches his canvas to a homemade mount in his smokeroom, a flat board dangling from the ceiling by a network of ropes and pulleys. Using a series of winches, he manipulates the board above, changing the angle and distance at the push of a button, allowing further control over the smoke’s interaction with the paper.

It’s a simple demo: a standard piece of paper for canvas and an identical sheet placed atop, this one with a broad circle cut out of the center and laid back atop, all held together with magnets. As I watch from a small plexiglass viewing window on the side, Tarbell stands grinning under his gas mask amidst his artist’s laboratory, burning shredded photo slides in lieu of credit cards (“I can’t keep asking for credit cards, people will wonder.”). Tarbell secures the flaming material at the end of a thin dowel, and within the airtight confines the smoke rises straight and true. Drawing the instrument back and forth under his paper canvas, the billowing column follows. This demo is a matter of moments.

Removing the outer layers, now a little charred, the picture is revealed – a dark black ring smoldering against the white backdrop, roiling and throwing off sooted waves like some ashen topographic relief, appearing simultaneously geologic and extraterrestrial. “Did I plan for this to happen exactly like that?” says Tarbell, examining the patterns. “No, but I created the direction.” Always looking for a new approach, Tarbell recently introduced silk screening to his process, which operates off the same principle of permission. Except, he says, you’re not supposed to burn a silk screen, which is much more expensive and survives the process at roughly the equivalent rate as the paper barriers, suffering “burnthroughs” on a regular basis. “The whole process is very punk rock,” he explains, “Making tools, adapting tools, using what you have and doing it differently than anyone else.” Far from concerned, Tarbell incorporates their demise into his work. His latest series, Failure to Appear, sees the artist recreating mugshots from gas station checkout magazines and the like. Each “print” results in a handful of burnthroughs, marring the subject’s visage with black scars. For each subsequent print, Tarbell will cover the burned section of the screen, erasing the error but blocking the smoke and obscuring the face further each time. “What’s interesting is that it became about history,” says Tarbell, flipping through the portraits of a young woman whose name and crime he cannot remember. “I block out her history, and her history takes over.”

“Any time you take a photograph, it’s that moment, and after that moment they can change,” says Tarbell, who describes Failure to Appear as something of a meditation on identity and the accumulation of that thing called self. This mugshot could have been a transformative process for this woman, he says, or not. She could have turned her life around, or not. Like a magician, Tarbell tries to capture that moment in a puff of smoke, but not necessarily reveal the answers. “You aren’t privy to that change,” he says. “The smoke is just a distraction.”