“The human instinct to be a predator is one of the strongest, and unless you get to hunt, it’s one instinct that a lot of humans never get to experience.” Matt Scarbrough, native Sarasotan, born and raised “living off the land” as he would say, is one of the premier hunting and taxidermy experts in the area, and the man behind Sportsman’s Guide Services. The hunt is in his blood, passed down from his father, a local ranch-hand of 34 years who raised his family on the carnivorous fruit of the chase, serving freshly killed game such as turkey, deer, wild boar, quail and squirrel at the dinner table night after night. “When I was growing up, it was about all wild game,” says Scarbrough, who keeps the tradition alive, teaching his own children–two daughters–the way of the hunt and to eat what they kill. “No preservatives, 100 percent all-natural–it’s like eating raw honey.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY EVAN SIGMUND AND SHANE DONGLASAN

AFTER BEING RAISED on game since childhood, Scarbrough finds he vastly prefers the taste of wild-caught meat as opposed to the supermarket offerings, all swollen chickens and marbled beef. It’s the old adage about how mom used to make it, except in this case mom killed it herself.

“Game animals have no fat in the meat,” says George Mazzarantani, a local attorney and hunter, tracking his prey as far north as the Arctic Circle and as far south as South Africa. “They’re very lean, so you have to know how to prepare it or else you’ll get that classic toughness.” Mazzarantani and Scarbrough are pals; it was Scarbrough who taught Mazzarantani how to bow-hunt and the finer secrets of preparing wild turkey. Ask Mazzarantani about Scarbrough’s wild turkey strip recipe and watch his eyes roll back. “Forget about it,” he says, lost in a delicious memory.

But it’s not all about taste; for Mazzarantani and Scarbrough hunting is a way of life, not one they get to indulge every day, but one nonetheless as richly philosophical and meaningful as any other part of their lives. It’s not about the kill, it’s about communing with and respecting nature and each other, and it’s about testing one’s capabilities and providing for oneself.

“People think hunters are killers,” says Mazzarantani. “We’re not, we’re conservationists. If you don’t hunt wisely and sustainably there won’t be anything to hunt next year.”Hunting wisely and sustainably means obeying limits, respecting seasons and following regulations and safety guidelines, like purchasing licenses and shooting responsibly. Those that don’t, Mazzarantani says, aren’t hunters, they’re poachers.

“From a conservationist standpoint, so much money from hunting is sent back to the site for conserving that resource we have,” says Scarbrough, citing the Pittman-Robertson Act, passed in 1937, which created an excise tax putting a percentage of all hunting-related expenses (buying ammunition, licenses, etc.) toward wildlife maintenance and rehabilitation as well as hunter safety classes. And in the state of Florida, hunting ranks No. 2, just under golf, in terms of expenditure. And there’s something primal and captivating about providing, knowing that the food on your family’s plate was wrestled from nature’s grasp by none other than yourself.

“When I was a kid, it was huge,” says Scarbrough. “I can remember feeling like I’d helped my family provide.”It’s another tradition Scarbrough preserves, taking special care to thank his daughters at the family blessing for their contributions to the family meal. “You could see that it made them step a bit higher,” he says.

But it seems the real draw is something nigh ineffable, something both Scarbrough and Mazzarantani struggle to articulate, the mystique of the experience when one is alone with nature, out of his normal element but falling back into instincts long dormant.

“Most people think of hunting as shooting and killing, but that’s probably five percent of it,” says Mazzarantani. “The real joy is in the experience–the anticipation, the camaraderie and being in the woods as the sun is coming up or going down and seeing the forest come alive. It’s nothing short of religious.”

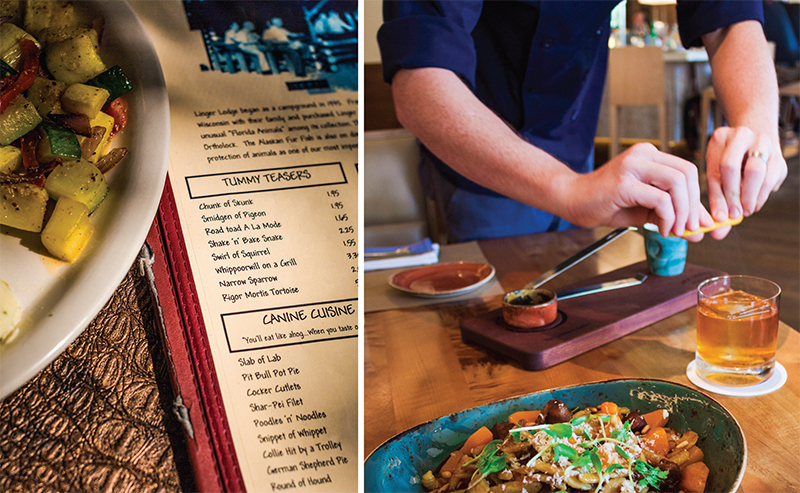

But if the hunt isn’t for you, that doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the fruits of the pursuit, so I headed on down to Linger Lodge Restaurant and Bar for a plate of their renowned gator ribs.

Formerly a hunters’ hangout nestled in the woods of Manatee County, abutting and overlooking the Braden River, Milwaukee transplant Frank Gamski purchased the lodge in 1968 and turned it into the restaurant that still stands today. Linger Lodge is that rare establishment, eschewing the siren song of the modern developer and embracing the Old Florida way.

A great wooden building, stepping over the threshold one might imagine they’ve stumbled through a portal to the past, to the days of trappers and frontiersmen, explorers and forest-dwellers. Timber beams crisscross the ceiling, festooned with rusty bandoliers, lanterns, kettles and sheaves of dried tobacco. A cracked and dusty harness looms heavy. Amongst the Old West detritus, a wall of badges and patches from law enforcement officers around the state and the country stands prominent, a salute from the Lodge and to it, as visitors continue to mail their emblems as tribute and thanks.

The real stars, however, are the countless animals dotting the inner landscape, hallmarks of Gamski’s penchant for taxidermy. More than 150 snakes lay frozen mid-coil, 72 bass gape open-mouthed from their mounts and hugging the wall by the door hangs the piece de resistance–a full-grown alligator, 12-14 feet long from snout to tail. A clothed mannequin leg dangles half-eaten from its toothy maw, a testament to Linger Lodge’s oddball sense of humor, which also explains the Jackalope and the Alaskan Furfish.

But don’t be fooled by the fun and easygoing atmosphere, Linger Lodge takes its gator ribs seriously, monitoring the process closely from catch to plate. Fresh gator arrives twice a week from Gators-R-Us, a Florida company specializing in wild-caught, live-delivered gator. You won’t find any farmed alligator here and nothing brought dead to the door, says Linger Lodge general manager David LaRusso. This ensures a fresh and clean taste to the meat.

“A gator will eat anything,” says LaRusso, who doesn’t like farmed gator because he can’t be sure what the animal has been fed and what flavors may have seeped into the meat. “But primarily four pounds of fish a week and that’s why it doesn’t become overly offensive.”For gator meat, pre-cooking preparation is key. At Linger Lodge, their prep guy has over 14 years of experience carving gator, and LaRusso says he’s one of the best, separating sinuet membranes from the ribs and removing unwanted connective tissue, leaving only pure meat, exposed and ready to tenderize in Dakin Dairy Buttermilk.

The next step is the application of a proprietary dry rub, the secrets of which LaRusso will not reveal. Other establishments opt for a sauce, barbecue or something similar— you can get barbecue ribs from Linger Lodge’s menu—but for the gator ribs it’s dry rub. Sufficiently rubbed, the ribs are slow-roasted for more than two hours, suspended above a pool of water, replicating a mild steaming effect and lending succulence to the meat. The end result is a beauty–tender, fall-off-the-bone meat under a crisp crust of herbs and spices, lending the mild, slightly fishy tasting meat a fiery kick. The ribs are naturally lean, meaning just about everything on your plate is ready to eat, without the fuss of separating gristle and fat and little to no tallow flavor.

“Most people are expecting something over-the-top,” says LaRusso. “But it really tastes like what you do to it, which is what makes gator an interesting product.”On LaRusso’s recommendation, I pair my ribs with some of Linger Lodge’s baked beans, LaRusso’s personal, secret recipe, which he claims is older than I am, and a Clean Slate Riesling to add a touch of sweet to the experience. It’s perfect, and I tell him so.

“Seeing is believing,” says LaRusso with a grin. “And tasting is better.”For another taste of game at its best, head down 301, swap the Braden River for the Bayfront and step inside Jack Dusty, where chef de cuisine Caleb Taylor has taken it upon himself to add boar to the fine dining selection with the Wild Boar Cavatelli.

“It’s a meat a lot of people aren’t familiar with,” says Taylor of his decision to include the boar, which he describes as having about one third of the fat of domestic pork. “Generally people are a little hesitant and then once they try it, they truly enjoy it.”Jack Dusty brings in its boar from a farm in Texas, opting for the shoulder of the animal and accepting fresh deliveries weekly. Taylor sears and braises the meat with his own selection of flavors and spices, including peppercorns, thyme, carrots, celery and onions. He’ll give the boar four hours in the mixture until satisfied with the tenderness and taste, when the meat is full and juicy and nigh falling apart.

Then the sauce. Taylor’s concoction is the understated star of the show. Taking fresh sage from Faithful Farms down in Palmetto, Taylor cooks it in a brown butter mix, heating the milk solids until brown, giving the sauce a nutty smell and flavor. Borderline frying the sage, the next step is adding the squash for a bit of sweetness and crispness. The type of squash varies with the season. When I stopped in, Taylor opted for fresh butternut squash, diced and delicious. The final major player in Taylor’s delight is the cavatelli itself, a gnocchi-esque pasta made in-house using a ricotta-based dough. Small and slender, with a texture hovering magically between firm and soft, cavatelli is perfect for holding sauces and flavors, with thick ridges cut into the side of each piece. You can find it frozen in the grocery store, but Taylor prefers to mix the dough by hand, pumping out the little morsels with a hand-cranked “Little Machine That Could” in the kitchen of Jack Dusty. Putting it all together can be a challenge in itself and it’s a challenge Taylor meets with gusto. The ingredients are expertly proportioned with everything meeting a pleasing ratio–not too saucy and not too dry, neither the boar nor the cavatelli nor the squash overwhelms and nothing is filler. The dish is topped off with toasted pine nuts, ricotta salata and petite radish sprouts.

“I like the dish because it’s very comforting,” says Taylor, who describes it as the perfect fall meal, not too heavy for the heat but heavy enough for a full and hearty feeling, a complement to a night in the crisp sea breeze.

As the final touch for a night at Jack Dusty’s, head bartender Ingi Sigurdsson recommends a classic cocktail. He says to avoid the citrusy drinks, warning of clashing flavors, and opts for the whiskey-based Smoking Jacket.

“Cocktails are aggressive, they have big flavors,” says Sigurdsson, snapping into action with what appears to be an acetylene torch. “Whiskey tends to be a little more in your face, a little rough around the edges.”Sigurdsson smokes the glass with some carefully scorched apple wood chips before depositing a single mammoth block of ice inside and pouring it over a mixture of Angel’s Envy Finished Rye, house-made burnt sugar syrup and a dash of Angostura Bitters for a spicy backdrop. The result is a surprisingly sippable and deft pairing. SRQ