Get Mark Famiglio talking about the Sarasota Film Festival and one thing bubbles quickly to the top—reputation. More to the point, the Sarasota Film Festival’s reputation as a “filmmakers’ festival” and haven for independent and socially conscious cinema. Corner him, and he can share stories about traveling the town with Woody Harrelson or talking industry trends with big-shot producers—and these visiting stars may be the highlight for some—but his passion lies with the films themselves, first and foremost, every time. “We never let the celebrities’ presence overshadow the art,” he says, and although some once viewed the festival as an international destination for glamor and glitz and the showy side of showbiz, to him that has always seemed costly, ineffective and beside the point of the affair. Some people take for granted the fact that a community will gather in a dark room to experience cinema together, but not Famiglio. There’s never a guarantee, he says, and that’s why festival content and film selection remains paramount, even to the point of sending his programmers from Sarasota to Sundance.

The film selection process has changed somewhat in the festival’s 20 years. Gone are the days of film canisters and film reels arriving by mail—everything is digital. Electronic submissions come in fast and thick, with the Sarasota Film Festival this year fielding more than 1,350 submissions from around the world by mid-February, a record number. A team of four programmers, including festival regulars like the smiling and bearded Greg Bortnichak and newcomers like New College grad Harrison Bender, watches each and every submission, with no exception, helped along by a committee of volunteers. Through this first part of process, just to be safe, each film will be seen twice. Working from these viewings, the four programmers then give a more studied examination of the top selections—another viewing!—and give their professional evaluations and recommendations. But amidst these thousands and thousands of hours of footage, what are Sarasota Film Festival programmers looking for?

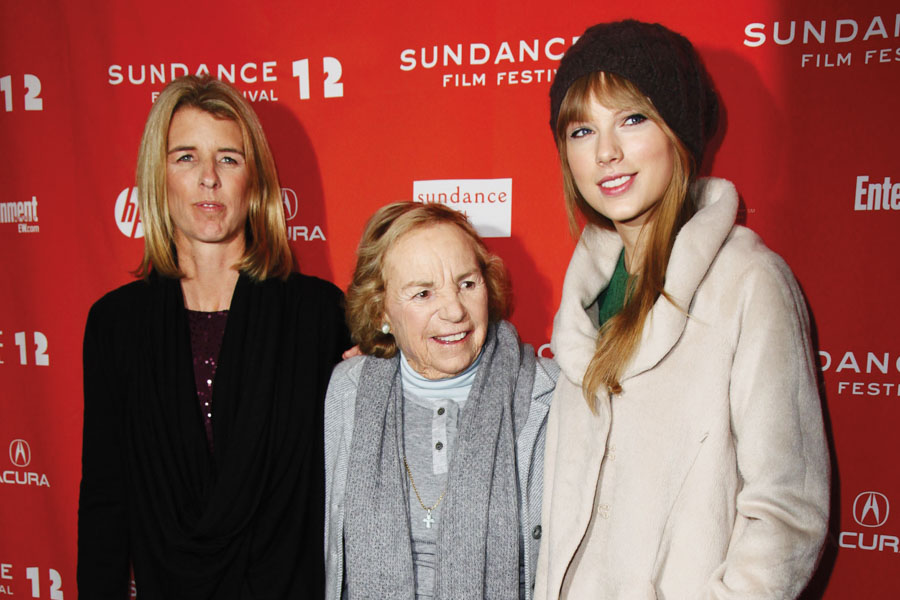

RORY KENNEDY, ETHEL KENNEDY AND TAYLOR SWIFT ARRIVE AT THE PREMIERE OF ETHEL AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL IN PARK CITY, UTAH ON JANUARY 20, 2012.

As an independent film festival, programmers focus less on the technical side of a production—those things most immediately affected by quality of equipment and access to professional resources—and more on the idea and the art of the execution. “The filmmaker might have a brilliant vision, but doesn’t have the funds to make it presentable for a multiplex audience,” says Bortnichak. “We need to really read through the production, to the heart of the film.” Unimpressed by big budgets, they’re not looking for a heart of gold—they’re looking for something original, whether in the concept, the screenplay or the presentation. “The eye of the filmmaker has to translate,” he says. Good acting remains key, and there are some technical considerations, but curating an independent film festival demands a certain amount of charity from its programmers and an agreement to meet the filmmaker on even footing. Many films are submitted as works in progress, with incomplete color correction or unfinished audio. To be clear, this doesn’t mean lowering artistic standards, merely understanding technical limitations. Bortnichak still expects to be impressed. “Even if there’s not a lot of money behind the film and you’re shooting it on an iPhone, you can still get good shots,” he says.

So what will disqualify a film from the Sarasota Film Festival? If it’s too old, says Bortnichak, or already publicly available, although the festival may bend the rules a bit if the film is only available overseas. What about content? Is there any content that makes a film outright ineligible? Bortnichak takes a deep breath. “That’s a difficult question,” he says.

Like acrobats at the circus, Bortnichak and his fellow programmers walk the tightrope of good taste. On the one hand, the last thing Bortnichak wants to be is a censor, which is pretty much unofficially recognized as the fascist of the art world, and not at all a good look for an independent film festival. But, on the other hand, the festival has to be responsible for what it decides to blow up on the big screen, and projecting pornography is still considered at least risqué, if not poor taste. “Often filmmakers will choose to present very questionable content,” says Bortnichak, “and we certainly don’t disqualify a film because of that.” But it does receive what the courts would refer to as something akin to “strict scrutiny,” aka is there compelling interest for the controversial material. “If we feel that graphic scenes of violence or sexuality are warranted and justified by the overall vision, then we’ll certainly consider it,” Bortnichak explains, though he acknowledges it does make the bar tougher to clear. “The film overall has to be really superb.” As Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said, “I know it when I see it.”

KEIRA KNIGHTLEY ARRIVES FOR THE 2005 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL PREMIERE OF THE JACKET AT THE ECCLES CENTER THEATRE, JANUARY 23, 2005.

Like the Greek gods of old, film festivals are an incestuous lot, and as much festival programming happens by attending other festivals to see what they’re playing as it does waiting on submissions from the filmmakers themselves. For Bortnichak and Bender, this means tickets to Sundance Film Festival. Coincidentally, this also means tickets to the snow-capped mountains of Park City, Utah, in the dead of winter. “Our experience as programmers is a bit different than that of the public,” says Bortnichak.

Far from a red carpet experience, the morning begins at 8am, with Bortnichak and Bender tromping through six inches of snow to the first screening of the day, which starts at 8:30am. With the festival spread across various venues—including a special theater open for industry professionals like Bortnichak—both Sarasotans brave the snow-swamped Park City streets to attend screenings until past 10pm, with only a quick lunch and scattered 15 minute breaks to stretch their legs, hit the facilities and, maybe, see some daylight. “It was a very full time,” Bortnichak says with a laugh, but with a sustained energy reminiscent of last-minute all-nighters that leave one jazzed but exhausted, like lightning gone slightly stale. It’s an urgency permeating the air at every film festival. “Because it might be the only time that you’ll actually be able to experience these films on the big screen,” he says, and he and Bender took a divide and conquer approach to cover twice the ground.

But just how does a programmer stay focused after the fourth day watching more than 12 hours of film a day? Are there special earmuffs that keep the brain from oozing out the ears? A special device out of A Clockwork Orange to keep one’s eyes peeled? Not really, says Bortnichak. “At that point, it’s really the job of the filmmaker to keep our attention,” he says, and any mind-wandering or sleeping likely counts against the film more than the programmer. Not that it mattered this time. “It was an outstanding year for cinema,” he says.

After deciding on a film, it’s largely a simple matter of approaching the filmmaker. Of course, there are certain films—typically larger, with big names and dreams of prestige—that aim only for a select few festivals before hitting the theater market, most look for as many screening opportunities as possible. “More often than not, filmmakers are artists and just want to give their work the best shot at survival,” says Bortnichak, “and get as many eyes on it as they can.” The end-goal is distribution, and each festival presents another shot.

Because it’s all about getting into that dark and high-ceilinged room, where the lights go out on an audience aligned like churchgoers in their pews, expectant and receptive, summoning a higher truth from their shared experience. “That’s the way filmmakers want their film to be experienced,” says Bortnichak. “And there’s really nothing like it.”