Art Center Sarasota had never applied for a grant from the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs before, but Lisa Berger, the executive director, decided to give it a shot this year. “Just for operating expenses,” she says. Just for a little help covering salaries and some other fundamentals, freeing funds for other projects. It wouldn’t be much, and it wouldn’t make or break the institution, but it could make a difference, afford a little more breathing room.

“Just a little help,” Berger says, for an arts institution that’s been a part of Sarasota just about as long as anyone—since 1926, to be exact—woven deep into the fabric of the community and still putting on shows as it looks to round the bend on a century. The team got together and submitted their grant proposal by the May deadline.

Three months later, Berger finds herself on the opposite end of the equation—sitting on a panel for a different group of grants, and reviewing submissions requesting state funds for multi-disciplinary events, i.e. fairs and festivals. Each application is scored. Many applicants are questioned. It’s an excruciating, maddening, marathon teleconference from which there is no escape, but Berger has reason to smile. Next to some of what she’s seeing, the Art Center’s grant is strong. Sure, these weren’t the same type of grants, but certain principles had to be universal, right? “And the information that we gave them was pretty good compared to the faults they found in other people’s grants,” Berger says. But the smile fades as the reviews end and time comes for the panel to determine who gets what and someone voices what everyone is thinking.

“Well, considering we didn’t get any money last year, we just went through all this for nothing.”

Every year, the Florida legislature passes a budget for confirmation by the governor. And every year—just about—that budget includes a hefty chunk of change to be distributed to arts organizations throughout the state, in the form of various grants. This number varies. 2014 saw grant requests fully funded to the tune of $36 million—a sizable jump from 2013’s $9 million. 2015 saw $33 million allocated. 2016 saw a small decline to $32.5 million, and, in 2017, arts and culture organizations across the state split almost $25 million, less than half of what was requested by grant applicants. But if there was a steady decrease to be noticed, it didn’t prepare local arts and culture organizations for the announced 2018 budget, which included only a sparse $2.6 million to be stretched between near 500 hopeful grant recipients. Some local arts leaders expressed their disgust and offense at what they saw as an insult, but, generally, people just wanted to know what happened. Last year, the arts and culture economy accounted for $4.7 billion in economic activity and more than 135,000 full-time jobs. “That’s kind of significant,” says Jim Shirley, executive director for the Arts and Cultural Alliance of Sarasota County. But the problem, according to Shirley, isn’t that elected officials or local representatives don’t believe in the arts or look to support them, but structural issues that leave state arts and culture funding more vulnerable than before.

Perhaps the greatest blow to guaranteed arts funding came in 2003, when the state changed the source of this funding from a dedicated fund all its own to merely being part of the general discretionary fund. Prior to this change, funding for arts and culture grants all came from a single dedicated source—late fees on business licenses. These fees could regularly bring in $40 million in a year, with all of it earmarked solely for arts and culture grants. In the current reality, arts and culture receives no special seat at the table and no guarantee, but instead must duke it out with the rest of them in a fight for a piece of the general fund.

This change, according to Shirley, was then exacerbated by a few things. One, the Florida Secretary of State had, six years prior, already been removed as a cabinet position, losing that special seat at the table, and is now appointed rather than elected. “And all of the funds for the arts sit under the Division of Cultural Affairs, which is the Secretary of State’s purview,” says Shirley. And if the Secretary of State loses any power, that means the Division of Cultural Affairs loses ground too. At the same time, a loss of dedicated funding meant an increased reliance on institutional memory—literally that legislators would remember that arts funding was now an active process and not a passive guarantee—that term limits could stymie at times, either by sun-setting important arts champions or introducing junior legislators who didn’t understand or missed the importance of arts and culture funding. In the early years, this wasn’t so much of a problem. “But unless there’s a strong champion for the arts,” says Shirley, “it falls through the cracks.” Lastly, the switch from a dedicated fund put arts and culture funding at the whim of politics. Sometimes that means a bumper harvest in election year; other times it means representatives from less art-centric counties seriously questioning why they should allocate significant funds for statewide spending that will not obviously benefit their constituents.

And as Florida found itself in times of tribulation—coming off a devastating hurricane and in the throes of an opioid epidemic as another school shooting brought student safety to the fore—the political will to fund arts and culture grants just wasn’t there. For several organizations in Sarasota County, that means tightening belts and making do with less, but most, like Berger over at Art Center Sarasota, have already learned not to count on state funding in the first place.

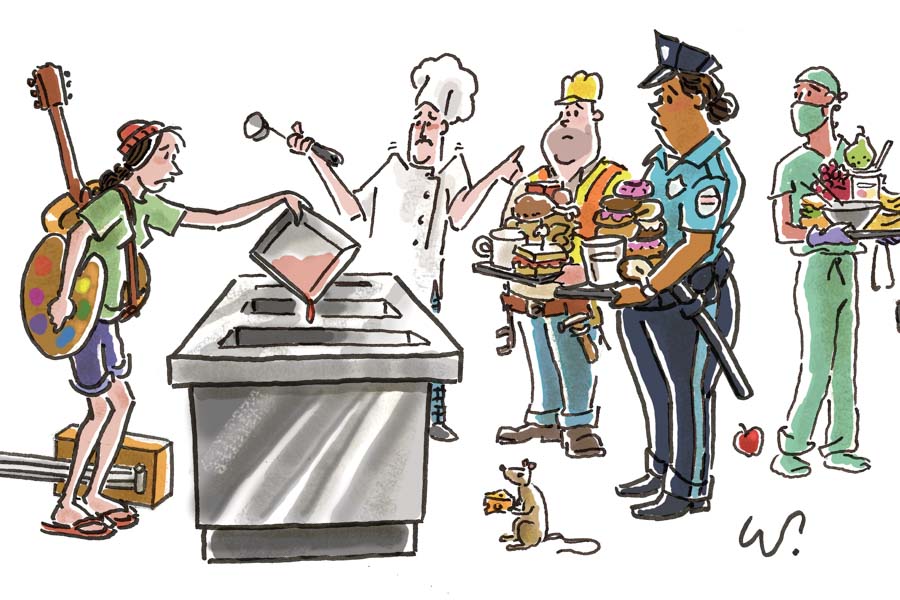

“We have learned over the years to not heavily rely on it because it’s always in flux,” says Sarah Wertheimer, executive director for Embracing Our Differences. Small in size and nonprofit by nature, EOD applies for a state grant every year and every year the grant is approved. But administrators never know how much the final grant will be. Some years it’s as little as under $3,000; other years as much as $34,000. But the funds always matter. “When we do receive these funds,” says Wertheimer, “it definitely allows us to expand our programming and offer these opportunities to more students. More kids can come on our field trips.” The latest budget shows Wertheimer that arts education is “clearly” not the legislature’s highest priority, and, though she accepts that survival and necessities take precedence over the arts, that doesn’t mean the arts aren’t getting less than their due. “We really do think that it’s a vital part of every child’s youth and every adult’s life,” she says. Janene Amick, executive director of the Manatee Players, takes a slightly different perspective. Every year, the Manatee Players does submit a grant, and, when it is available, the grant goes toward operating costs. “It can be a meaningful contribution,” says Amick, but not one that the organization relies on, expects or even feels should always be granted. “I don’t believe that any organization should put all of its eggs in one basket,” she says, “so it does keep us mindful that during the course of what’s going on in our society, some things to have to take precedence over others.” Florida is a balanced budget state, Amick says, and she appreciates and respects that. And with the state currently looking like the epicenter of an opioid epidemic and a growing hub for sex trafficking, Amick does not question the decision to fund those fights as opposed to the arts grants program. Especially when some children still don’t have food to eat. “I’m sitting across from the director of Manatee County Health Services and I’m sitting across the table from the food bank and we only have three dollars at the table,” she says. “Where should we put our dollars?”

But that doesn’t mean Amick doesn’t want to see state support for the arts, or even that it necessarily must come second to or distinct from other missions that the state must undertake. Instead, arts programs can go hand-in-hand with mental health programs, community building and addressing specific social ills. “They’re just now researching how music therapy helps PTSD,” she says. “I believe that putting funding strategically in the arts and these types of things will help overall.”

For now, state funding for the arts remains a yearly battle to be lost or won in the halls of the legislature. Outside of constant advocates like Shirley, grassroots efforts to raise the profile of the arts in state funding break through into the mainstream now and again, typically in response to an already landed body blow to the budget, but sustained lobbying becomes difficult to achieve when already underfunded and running on volunteers. “I’m not aware of any civic movement in our community yet,” says Wertheimer of the current situation, whose two-person staff leaves little time for legislative outreach or tangential coalition-building. “But we would definitely be open to seeing what others are doing,” she says.

Shirley would like to see more state funding, but loses little sleep over a bad year. The same things that got local arts and culture organizations through the recession—professional management and a grand philanthropic tradition—have prepared them for years like this, he says. And even if the folks in Tallahassee don’t see the need to support arts and culture in Sarasota and Manatee counties, the people here know what it means for the community if the artists were to leave. “We’d still have a beautiful beach and we’d have nice weather,” says Shirley, “but it sure would be a lot more dull.”