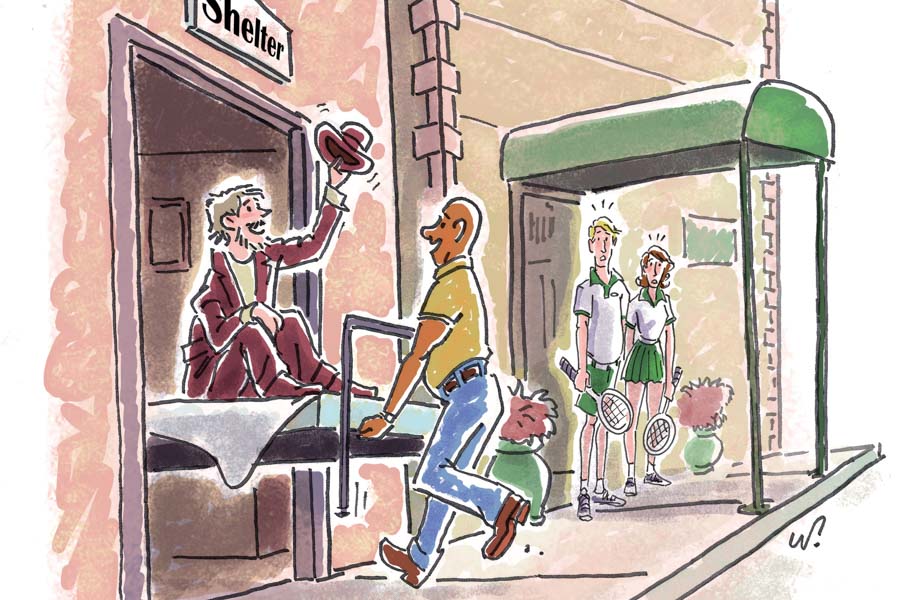

The problem of chronic homelessness for years perplexed and separated leaders based on favored solutions. But officials say that now more than ever, everybody tackling the issue of taking impoverished individuals off the streets seems to be working in concert. “There is nothing recognizable about the system we have in place today from what you saw two years ago,” says Jon Thaxton, Gulf Coast Community Foundation senior vice president of community investment.

ILLUSTRATION BY WOODY WOODMAN.

What’s changed? Today the Salvation Army sets aside dozens of shelter beds with fewer restrictions on entry than ever before. Permanent housing options have slowly popped up around the region with the hopes of bringing perpetual transients off the streets for good. And hot-button words like “wet shelter” and “housing first” have slowly disappeared from public dialogue, even as the core concepts behind the practices get employed with broader use than ever.

The approach aims to make more meaningful progress in ending homelessness. “Everyone has been doing good work for years,” says Ed DeMarco, CEO of the Suncoast Partnership to End Homeless. “It’s not a matter of effort. It’s a matter of focus.” The notion of moving former street-dwellers into new housing projects en masse, of course, still holds the risk of angering neighborhoods. But as experts and advocates moved the conversation outside of heated commission chambers, more progress has been made as headlines about conflict disappeared.

Housing At Last

Community leaders in January announced a new venture that promised to finally bring dreams of housing the homeless into a manifest reality. Philanthropic leaders trumpeted a $1-million investment in rapid rehousing for those defined by Housing and Urban Development as chronically homeless. Foundations now fund a partnership with St. Vincent de Paul CARES, a social services agency based out of St. Petersburg and the largest rapid rehousing provider in Florida. Along the way, other housing efforts from the likes of Jewish Family & Children’s Service of the Suncoast to the newly announced venture in Sarasota also seek to put a roof over the head of individuals sleeping in alleys, but Thaxton calls the St. Vincent de Paul project one of the most significant steps forward.

The effort expects to pull 135 individuals now living without homes in Sarasota County and get them set up in apartment units scattered throughout the region. The rehousing initiative will target chronically homeless, defined by Housing and Urban Development guidelines as those living continuously in homeless conditions for a year or those with some disabling condition who have four episodes of homelessness over three years. DeMarco hopes the program will be the “tipping point” in managing chronic homelessness. This new venture means additional dollars and manpower to find the chronically homeless and move them into housing. Then, case workers will provide “wraparound services,” from skills and job training to alcohol and drug rehabilitation. This launch happens as a taskforce for the Suncoast Partnership makes a renewed effort at addressing homeless populations in Sarasota and Manatee counties.

Michael Raposa, CEO of St. Vincent de Paul CARES, says the new program intends to remove as many barriers as possible to individuals, especially those who may be ineligible for other social services. “You don’t need to be clean or sober. You don’t need a job,” he says. “This is a holistic approach to ending homelessness for this client.”

But Thaxton says the effort can only work thanks to an ecosystem of other homeless initiatives put in place to address homelessness in holistic fashion.

An Ecosystem of Support

Sarasota leaders at the height of conflict with the county made clear they would not like to see a come-as-you-are shelter, as proposed by consultant Robert Marbut in 2013, in the city limits, originally conceived as a central facility with some 250 beds for those individuals not admitted into other shelters in the region, which at the time barred entry for the intoxicated and frequently banned individuals with criminal tendencies. But while a new shelter in the city seemed a no-go, Thaxton says social advocates still saw the need for beds in the area where every social service helping impacted individuals already conducted business.

“City commissioners said no new facility, so, with my redneck logic, I says what shelter do we already have?” Thaxton says.

Starting in April, a new lease between the city of Sarasota and the Salvation Army set aside 50 beds in its existing facility that would be low-barrier entry and serve a similar purpose to the shelter once proposed by Marbut. Sarasota City Manager Tom Barwin explained to commissioners in the fall that the beds would be used in emergency situations to get people off the streets, but the city would have priority on those beds, and the Salvation Army could not simply turn away placement of chronically homeless individuals in favor of other clients. “These are our beds for a homeless crisis response system,” Barwin says, “and the Salvation Army is really hosting the beds and providing space only.”

But that helped establish a model, Thaxton says, for other governments to approach the agency, and now the use of beds seems so successful that organizations are lowering barriers all around. The only thing that can keep someone from getting space now, Thaxton says, would be violence.

In order to get a working system, Thaxton says all parties have now established access points throughout Sarasota County, building on the success of local law enforcement Homeless Outreach Teams. The HOT teams in the city of Sarasota and in Sarasota County reach out directly to homeless individuals to connect them with social services. Thaxton says those teams, along with recent contracting by the city of emergency shelter beds at the Salvation Army, make housing the next appropriate component.

Raposa says the goal of rapid rehousing at St. Vincent de Paul CARES then gets individuals into apartments within 30 days of accessing the program, though he noted it could take time to reach that level of efficiency. A similar effort by the organization in Pinellas County over the years has cut rehousing times from about 60 days in 2012 to about 33 days now.

“I cannot tell you how many hours of work are invested in this partnership,” Thaxton says. “[Homelessness] has a demonstrable impact on our local economy, creating a deterrent to doing business downtown. It’s amazingly costly to law enforcement, the judicial system, Sarasota Memorial Hospital, other healthcare providers. We are spending tons of money, and it’s a recurring thing every year.”

Pushback

But that’s not to say everything has gone smoothly in terms of providing for housing for the very poor. Sarasota officials a couple years ago heralded an agreement with Harvey Vengroff, a developer specializing in affordable housing, to open a 200-unit complex of small apartments in a former hotel near downtown Sarasota. This spring, Vengroff announced difficult approval processes at the city made the project impossible to pursue, and he’s now getting ready to sell the land to a luxury condominium developer instead. “I spent 10 years trying to get affordable housing,” he says, “but the city said they would prefer some wealthier people.” Vengroff says he’s done trying here, and will instead pursue projects in unincorporated Manatee County or in cities like St. Petersburg and Orlando.

And another city project recently came close to falling through. Planning commissioners in February unanimously approved plans for a project from Blue Sky Communities and Community Assisted and Supported Living to open an 80-unit mixed-use project on Fruitville Road, where half the units would be leased to homeless and disabled individuals. “We came up with something that would be an asset for the city,” Shawn Wilson, president and CEO of Blue Sky Communities, told planning commissioners.

But when neighbors grew wary of the potential of 40 ex-transients moving in next door, land-use attorney Dan Lobeck petitioned the City Commission to nix the project. “This is a population with significant potential for problematic contact with neighborhoods,” Lobeck told SRQ. “Even if we weren’t talking about diseases such as schizophrenia and about active drug users and alcohol abusers, that density is a problem.” Ultimately, the project barely survived a 3-2 vote in April.

Still, Thaxton remains optimistic, in large part because leaders have found solutions to many problems outside the political arena, where public opinion can step on the ability to solve problems from a dais. A philanthropic donation spawned the St. Vincent de Paul project, and cooperation between a private developer and a company with a history of helping the homeless created the Arbor Village effort moving forward on Fruitville. Organizations like the Salvation Army and Resurrection House working hand-in-hand with human services agencies tackling addiction and poverty remain the partnerships getting things done today. “This was always billed and always put together as a systemic approach,” Thaxton says. “We have gone about numerous ways to get people off the streets, and it’s working now.”