Way back when, in a strange period of the before times known as the 1970s, a young art student named Tom Casmer traveled with his class from a small arts college in Minnesota to the urban wilds of New York City and the studio of the acclaimed sculptor, Louise Nevelson. For Casmer, this was before the wife, before the kids, before 20 years of teaching at Ringling College of Art and Design, and before a trademark white beard that Rasputin’s own ghost would envy. But it planted a seed, long-germinating for nearly 50 years, that finally came to bloom last year in the shadow of a global pandemic.

At age 70, Casmer is just getting started.

Fresh off a successful cataract surgery, his vision is better than it’s ever been. Retired from 20 years of teaching at Ringling College, he reclaims his days as an empty canvas for his creative impulses. And, after decades of sketching and painting and printing, the budding sculptor finally realized that constraining oneself to merely two dimensions is for the birds. Or, at least, someone else. “I’m just now figuring it out,” he chuckles. “Interesting times.”

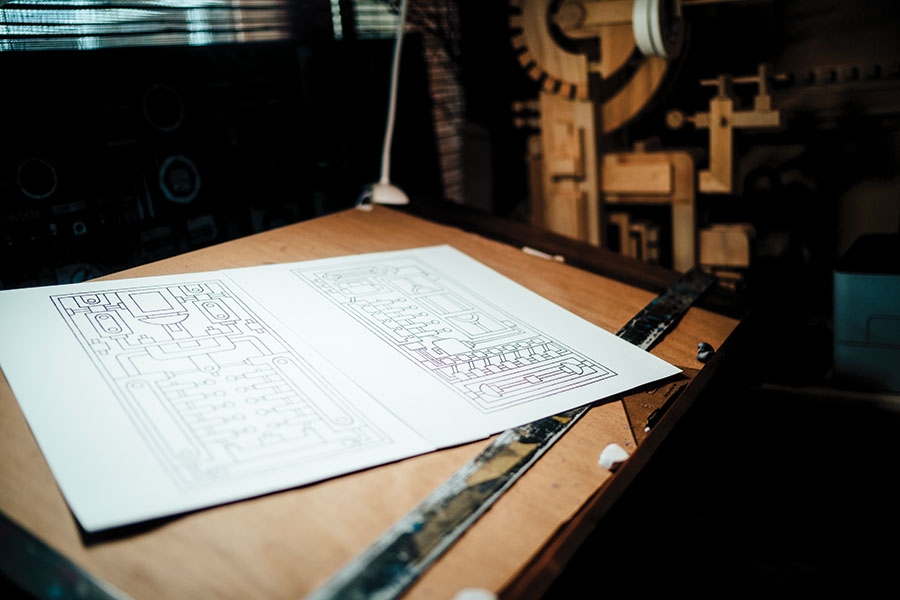

Though he is known for his intricate drawings and prints—looking like everything from fantastical blueprints for Neo-Aztecan ray guns to detailed schematics of a next-generation combustion engine, or perhaps even the inked ravings of the last disciple to some stone-age robotic religion—this last year has seen Casmer take his art to the next level. Literally. Converting the family garage into a makeshift woodworking studio, Casmer has begun bringing his creations to life, handcrafting almost 30 of his sizable “wall relief sculptures” in little more than a year.

The transition has been long coming. And Casmer estimates that the past 45 years of his life have been, in some way or another, building to this point in what he now considers to be one great artistic conversation between himself and his work. It’s a conversation he has nearly every day, with every new piece, and he can’t be sure where it’s going but he does know that these chats are getting longer. And, as in every conversation, it begins with the first line.

Sitting at the desk in his home studio—a narrow converted breezeway with reed blinds on the windows and walls covered in carven sculptures—Casmer takes a small piece of Bristol paper and a pencil and begins to make marks. He formulates shapes. He has no plan. He is a seeker and if he knew his destination then the act would not be one of exploration and Casmer has no time for such scripted conversations.

He has faith in the line.

“Color could go away,” Casmer says. “I don’t care, as long as I have line.” Alone with his Bristol, Casmer lets his pencil loop and whorl, dash and divide, throwing shapes and catching them as they come, the many lines forming a little world seeming of its own creation. It’s a remarkably organic approach to what will result in something distinctly mechanical and aggressively geometric, but the process—the conversation—serves its purpose and rewards the dutiful, with the resulting image as much a revelation to the artist as anyone else. “Who knows where it all originates,” he says.

But, once discovered, the line must be preserved, and so Casmer will tend to his line twice, revisiting each mark with heavy ink, reinforcing graphite shades with black permanence to create a final stark image that will serve as a blueprint for the next step. “It can be tedious but it’s also meditative,” he says. “It’s a conversation. And, in the process of inking, I’m envisioning the construction and looking at the relation of the shapes and how that’s going to come together.” There’s also the beauty of the blueprint itself, which makes it more than just a step in the process. “I’ve always been fascinated by blueprints, schematics and circuit drawings,” Casmer says. “I don’t understand them; I’m just fascinated by the line on the paper.” It’s a fascination that the boy who wished he had X-ray vision has had since childhood. He retains it now as the man who likes to walk unfinished construction sites and can be seen at traffic lights with his phone out, snapping pictures of the esoteric landscape of nozzles and knobs and dials and hoses on the back of the tar truck in front of him. “It’s the infrastructure—what’s under the skin—that’s really of interest to me,” he says. “I’m drawn to those shapes.”

As to what those lines and shapes represent—a map to hidden truths, the strictures of an unseen order, or perhaps a paean to the sublime beauty of potential itself, frozen as if in amber—Casmer offers no opinion.

He’s busy building. Previously, this is where the conversation would end, with the blueprint’s potential flattened onto a print, colored on the computer and brought to some sort of half-life on a handbuilt box frame. These days, Casmer slaps the blueprint on the door of his garage-come-woodshop and the conversation continues over the whir and whine of myriad saws and sanders.

Like a painter collecting brushes, Casmer dove into the woodworking world headfirst after first crafting a small totem for the Shopliftable show at GAZE Modern in 2019. He has since assembled an array of new toys, including a jigsaw, circle saw, table saw, chop saw, miter saw (for delicate cuts), belt sander, nail gun, pin nailer, assorted drills, a whole bevy of mismatched clamps in different sizes and a shelf full of rulers and protractors and other measuring assists. And a pair of tweezers. “Tools change,” he says. “But the work…” and he trails off.

With the blueprint on the wall, Casmer begins to build. With the piece laid out in the center of the space like a patient on the operating table, he works in poplar and pine—nothing fancy—and leaves his mark on every piece before it becomes part of the sculpture. “Everything you see is hand-cut in some way, shape or form,” he says. And though he follows the blueprint closely—including taking measurements from it for scale—the creative process never stops. The shapes still talk to him and he listens through the noise of their construction.

“I start to jam on it a little more when I start constructing,” Casmer says, and sometimes that does mean deviating from his blueprint. “It just kind of lets you know when what you have drawn initially and thought was OK needs to be rethought.” None of this indicates any sort of mistake in the creation of the blueprint, but merely acknowledges the fact that Casmer’s work has entered an uncharted dimension where his map serves no further purpose. He has to think in terms of elevation and depth, heft and shadow. He returns to the conversation in faith that his relation to the work will guide him. “At a certain point, you’re improvising,” he says. “It starts to inform itself and you’re reacting to what it’s starting to become.”

The end result stands as something liminal, occupying the space between print and sculpture and, at their best, manifesting the strengths of both. The line has been given form. This one looks like a giant circuit breaker; that one some sort of Sisyphean pinball machine with no clear path to victory or defeat but four suspiciously sperm-like shapes that could all too easily represent the artist’s four children. (A statement on parenthood, perhaps?)

And the sculpture on the table, awaiting the last finishing touches, Casmer has named In Response to Leia, as his own tribute to the impact, however long delayed, that Nevelson’s work has had on his artistic journey. A nod to someone who left the light on to lead the way for travelers like him.

“Drawing and painting have always been a struggle for me,” he says. “This is a struggle, but, for the first time, it feels like an actual fit. I don’t question it. I don’t judge it the way I did my drawing and painting. It feels like the right medium for me.” SRQ