Philomena Marano’s older cousin, Nora, used to drag her around their little corner of Bensonhurst like she was a circus curiosity. “Phyllis,” as Nora used to call her, “draw a horse,” and draw she would. With a bottle in one hand and a pencil in the other, baby Marano cranked out not some crude assemblage of shapes lacking any connection to an actual horse, but a sketch with identifiable proportions that told a story. That same steady hand went on to pick up pens, crayons, markers and paint brushes all through afterschool art classes, fancy Manhattan magnet schools and the illustrious Pratt Institute (where she campaigned to be the first-ever “draw’ring major,” as she says proudly in her Brooklynese).

She went on to work with Robert Indiana—yes, that Robert Indiana—helping him produce the prints that came to define a whole pop art movement alongside Warhol’s product portraits, Johns’ American flags and Rosenquist’s pop montages. It was during this time that Marano picked up the two most important tools that would come to define her career. The first was the notion that no object was too mainstream or mundane to be creatively rendered. The second: an X-Acto knife.

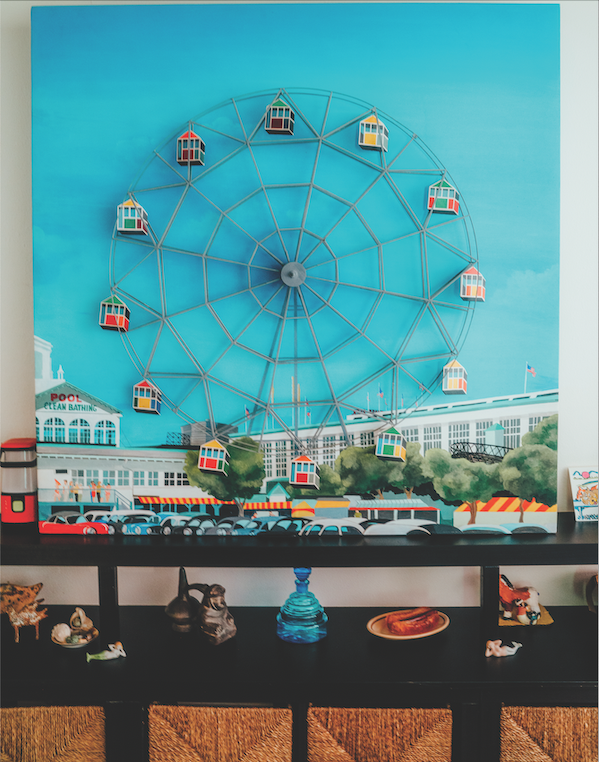

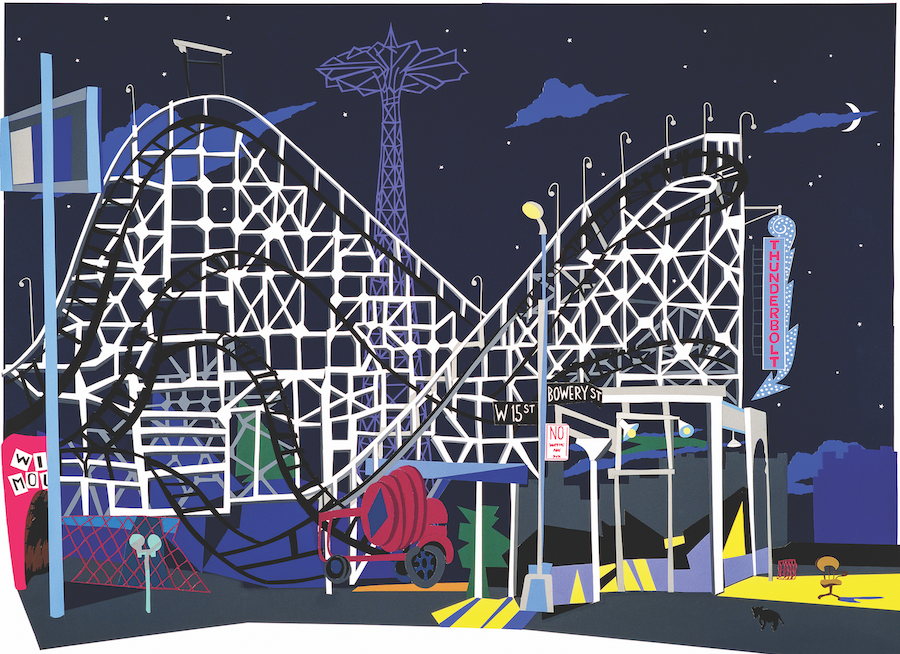

“Robert used to talk about riding in the car with his mother and looking at all the highway signs,” says Marano, “and he used to call them ‘highway literature.’” She got to thinking about the iconography that made an impression in her own life and turned to the mythical, whimsical, distinctly American temple of amusement known as Coney Island. Like many New York City children, Marano grew up steeped in bumper cars, roller coasters, spook houses, snow cones and ice cream. She grew up enamored of the colorful signage, the banners waving in the wind and the danger of the Parachute Jump. “There were archetypes embedded in the culture there,” says Marano, “it really had its own mythology.” When she finally put all of these elements and implements together, she created Shooting Gallery #2. Made from hand-cut paper, it depicts a carnival shooting gallery from the inside, rendering all of its gears and moving parts in the brilliant silkscreened colors of the Color-aid line of paper.

Though the piece captures her precision and attention to detail, her later work, like the American Dream-Land series, would grow in complexity and depth. Her process begins with a drawing. “Even though I’m cutting paper, drawing is the root of all of it,” says Marano, “it’s all so dependent on the lines, whether it’s a pencil or a knife.” She sketches her image onto vellum paper with a pencil, which becomes what she calls her “master tracing.” From there, she carefully plots out the layers and colors of the piece, starting with the background and slowly shifting to the foreground, accounting for shadows and texture and color along the way. Using the master tracing, Marano cuts each swirl of a cloud or rollercoaster truss with the X-Acto knife, checking it against the tracing to ensure each piece fits together properly.

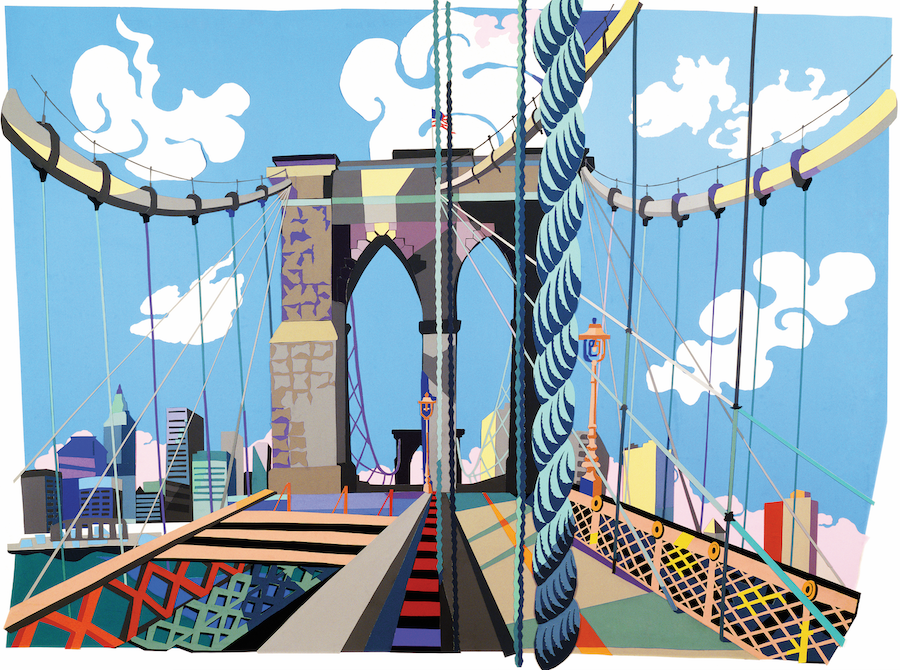

The full scope of that complex and tedious process looms large in I Hear the Brooklyn Bridge Singing, which depicts a view from the bridge’s central walkway. The texture of the steel cable in the foreground stands out with its careful depiction of the cable’s braids. As the eye delves into the background through the arch, the trusses and windows in the buildings stand out as particularly tedious objects with which she captures the depth of perspective in the scene.

Since her move to Sarasota in March 2017, she continues to celebrate Coney Island’s storied iconography but has added a new wrinkle to her subject matter. At a recent survey exhibition of collage at Ringling College, Marano showcased some works that depict The Nerveless Nocks, a Sarasota family of circus performers who travel with their motorcycle acts all around the nation. “It has a very similar kind of excitement and mystery as some of the Coney Island rides I remember,” says Marano. In Vortex of Doom, Marano depicts a high-flying act as seen from the ground, with blue skies and big white clouds in the background. In a sense, it captures the entirety of her approach. It’s a scene of whimsy and majesty, of danger and fun, of rich color and hard-edged lines—captured lovingly, painstakingly and with childlike wonder on paper.