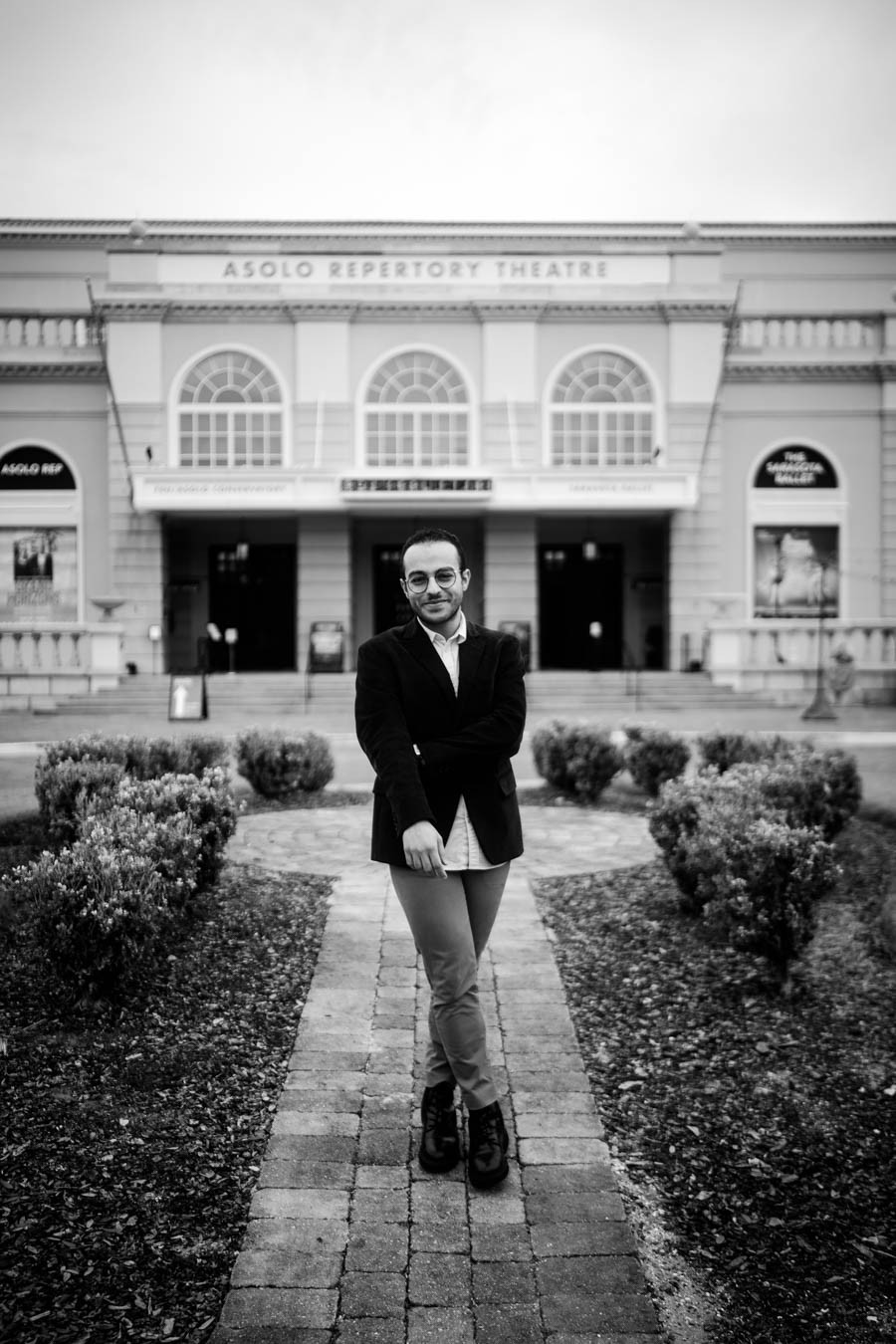

In Sarasota, a new voice in theater has arrived— one with a breadth of experience so different, that the worlds he curates give us no choice but to reflect upon our own. Adam Ashraf Elsayigh entered into his first season as Literary Manager and Dramaturg of Asolo Repertory Theatre this past November. An Egyptian immigrant and playwright, Adam’s award winning plays for example Revelation, which garnered the Himan Brown Playwriting Award, have explored how immigration and queerness complicate the American identity. He sat down with SRQ to discuss his unique background and how his artistic vision influences his new role at Asolo Repertory Theatre.

SRQ: You grew up in a Muslim household in Dubai, but had access to American cable television and attended a British school. How does this intersection of culture inform who you are as an artist and what you do as a Dramaturg?

Adam Ashraf Elsayigh: It informs everything that I do. I grew up in a lot of different places, each one informing how I think about the world and how I curate new stories. When I first came to the United States, I struggled with the label of being an ‘American playwright’ or ‘Immigrant playwright’. I eventually realized that being an immigrant is part of what makes me an American playwright — I’m writing about subjects such as immigration and queerness that have not historically been perceived as American. As both a playwright and Dramaturg, I aim to complicate the American identity. When developing new plays I ask myself, “How are we engaging the subjects of immigration? Are our plays all Americana plays? What does it mean to work with immigrant playwrights? How are we depicting nationhood?”

What will you be doing as Dramaturg and Literary Manager at Asolo Rep?

I define Dramaturgy, especially in my role at Asolo Repertory Theatre, as cultural translation. That process takes shape over three different phases. The first phase of my role happens when the play is still in development. When describing a Dramaturg to a non-theater person, I always will say, “When a novelist submits a first draft of a novel to a publisher, there is someone who analyzes it. They analyze the novel’s structure, what it means, and how the reader will react to the novel before giving feedback to the novelist.” That’s what I do with plays and playwrights. As a playwright myself, I’m trained in play structure and analysis — understanding what the engine of a play is. I love working with writers to help them reach the best, most vulnerable, most exciting and most dramatic version of their work.

The second phase happens once play is locked and is being developed for production. I’m supporting the creative theme, from the actors to the director. On the institutional and theater end, that also means that I’m often supporting creative teams as they are trying to realize, trying to decode, to understand, to interpret the text. For example, in our upcoming production of Our Town, a play written in 1934, but set in 1901, much of the language is not language that we use anymore. Providing the actors with the modern equivalent of that language informs how they move through and process the text. Finally, the third phase — where the most traditional definition of the term takes hold — occurs when the play is set to release. The term “dramaturgy” comes from a theory in the 19th Century German Enlightenment which argues that everything that happens from when the audience hears the title of the play to the moment they leave the theater, is all a part of the experience of the play. My job is to curate that experience—empowering the audience with knowledge, notes, and ideas that help them better digest the play. It’s putting the text in conversation with the larger world.

How do you curate the audience’s experience?

It could look like 100 different things from creating the playbill to crafting the email audience members receive when they purchase their tickets. If it’s Our Town, that email will include a video on what it was like to live in 1930s New Hampshire. If it’s Grant Horizons, there might be a virtual tour of the retirement home the characters live in. At the theater, it includes curating the talkbacks — what is the audience’s experience and how are we taking them on a journey beyond the text? It’s all about finding innovative ways to connect the audience to the play. If you’re doing a zoom production, for instance, it’s creating a way for audiences to engage with each other when they’re alone in their apartments.

How would you balance the operational aspect of putting the finishing touches on a play with working on new play development?

Our Producing Director Michael Donald Edwards told me that, “There’s no set job description for a dramaturg because you have to take on the role and decide what it means for you.” I think if you interviewed every institutional dramaturg in the country, their day to day of their job would look very different. At Asolo, because we are a producing theater, much of my focus tends to be on supporting the creative team and supporting the audience element rather than working with playwrights on developing the text.

That being said, my background as a dramaturg is primarily in new play development. It’s working with new plays and cultivating emerging writers. Part of what drew me to the Asolo was the chance to foster new play development in an institutional theater. Our Ground Floor series, which happens concurrently with every season on our main stage, gives me the chance to do just that. It’s focused on the development and workshopping of a play—not to serve a final product but to support the playwright.

Can you walk us through the season selection process at the Asolo Rep and how a script moves from development to production?

I’m not in any way the ultimate decision maker — Michael Donald Edwards is. However, season selection is a collaborative process. Michael, Celine Rosenthal, our Associate Artistic Director, and I will read probably 70 or 80 plays before we land on the six, seven, or eight that we produce. We will each meet on a weekly basis and discuss our thoughts on the plays we read and if they’d be good for our audience. Each of us could not have more different tastes from one another—which has made for such a wonderful learning experience. Regarding production, every play is different. Some plays are two-handers (only two main characters) that don’t require a set and the playwright submits a really great first draft. More often than not, however, plays will take a solid five years of development along with countless hours of workshopping. Because of scarcity and the numbered reality of our world, not every great play will be developed. Not every great play that gets developed will be produced. You just have to enjoy the process itself. If you don’t, you’re always going to be unhappy in the theater.

How do you guide playwrights to a space where they can create their most vulnerable and authentic work?

First of all, it’s making sure that I am not writing the play, which is to say I would never sit a playwright down and tell them, “This character is not working, because what they really should be doing is this.” Instead of me saying, “No, that’s actually not what you want to do,” what I would say is, “Tell me more about why. Why does this character have to take this action?” Perhaps the most important skill of being a dramaturg is knowing how to ask really good questions. That process involves gaining the artist’s trust while also trusting their vision. I want to be someone who’s helping them write the play that they want to write instead of someone who’s forcing them to write the play the “correct way”.

Additionally, I try to create spaces that are conducive to the playwright doing their best work. I don’t believe that you should only write what you know, but I do believe in helping the playwright understand the context and culture of their story’s setting. In the writer’s room, I want to bring in people with the right identities and cultural knowledge to help tell the story most authentically. That could include the addition of a cultural consultant, another dramaturg, or the correct actors for the roles. This process applies when telling stories set in any culture, regardless of race or background — I need to know the limitations of the playwright’s knowledge, so that I can bring in the right people to help best serve the story.

In your writing, you’ve mentioned that you’re often rendering people who haven’t had a chance to be fully represented and that intersect with your own experiences. How does that inform new stories?

When I came into American theater as an immigrant and a playwright, I had this grandiose artistic vision of wanting people who look like, sound like, or share some identities with me to be represented on stage. That vision, however, didn’t coalesce with the productions of institutional theaters — traditionally, the dramaturgs at such establishments are not people who look like me or share my experiences. That made me realize that to carry out my vision I couldn’t just be a playwright, but needed to be a curator and an artistic producer as well. That same impulse informs why I want to produce something like the Ground Floor series. It informs why I’m interested in curating and being a part of the spaces that I get to be in in this role. However, I’m cognizant that the stories I want to advocate for and that I want Asolo to present are going to be culturally different from who our audiences are. The question then becomes how do we tell these stories in ways that not only translate to and excite our audiences, but also make them feel like they’ve been changed by the experience?