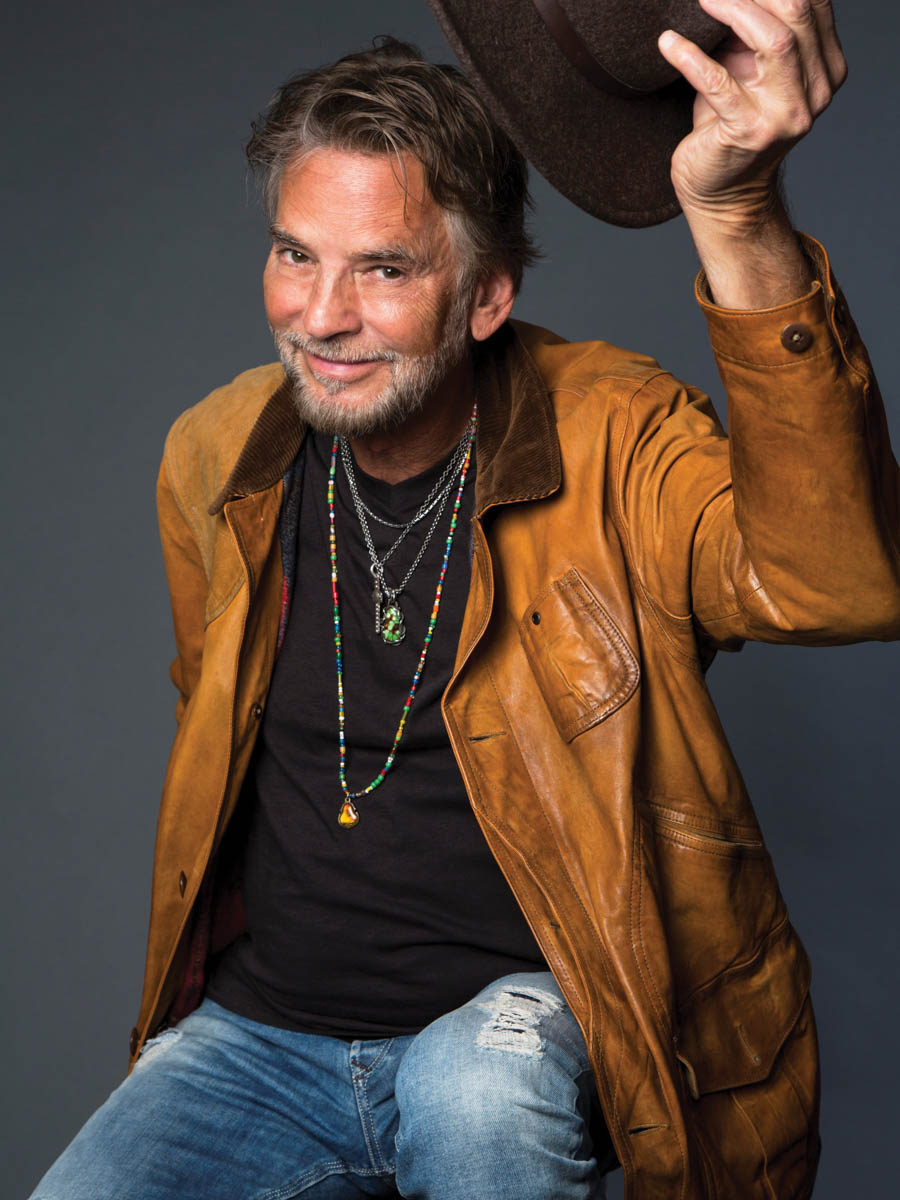

On March 10th, Grammy award-winning artist Kenny Loggins will kick off his final concert tour with a performance at the Van Wezel Foundation’s 2023 Inspiration Gala. Loggins has sold more than 25 million albums worldwide with chart-topping songs that have entertained generations of audiences. He sat down with SRQ to share memories of his decades-long career and his feelings about his upcoming final tour.

What prompted the decision to embark on it and make it your final tour? KENNY LOGGINS: This is my finale. I keep getting asked the question of why but the answer is really simple. I’ve been on the road since 1971, travel is becoming difficult and I’ve just felt that I've reached a point where enough is enough. I love the audiences but as Dan Fogelberg said in one of his songs, “The audience was heavenly but the traveling was hell” and it can be. Last time I went out I caught Covid twice, so hopefully that won’t be happening again this time. I figured I should go out while I can still hit the notes and still sing the songs and not wait until that's not possible which can be really depressing.

What emotions are running through you while on this final tour? LOGGINS: I haven't really dealt with the emotions of realizing that “this is it” as we used in the ads. I know that it’ll hit me once I reach the audiences that are super appreciative and get the depth of what this last show is for them, then that in turn will get it for me. I know that there’s going to be some emotional reckoning, but I feel like I’m ready for it. In my dream of dreams it has to do with being the final farewell that’s filled with emotion and gratitude in both directions.

What motivates you to continuously perform? LOGGINS: A number of reasons: a couple of divorces are certainly motivational. I’ve had to rebuild my personal finances twice, I have five kids, their needs continue—college leads to starting a new business or moving into a new territory. I want to make sure I have enough to retire on and take care of me and the kids. One of the primary reasons I didn’t quit as well is the interaction with the audience. It feels so good when they sing along with you at every show and you get to realize that that 50 year career has a payoff—it's the connections that have been made and the realization of the importance that your songs have in other people's lives—and that’s a real thing. I think that most of us get into the business because we want people to appreciate our music, we spend our entire lives getting people to hear it, and this is the point in the career where you get to see the payoff for that investment, you get to have that connection with the audience.

What was it like when you didn’t have that preexisting connection with the audience, when you were starting off with Loggins and Messina in 1971? LOGGINS: That’s a completely different rush. You’re going out there, you don’t know how it's going to be received but because we’re young and naive, we’re extremely optimistic about what’s going to happen. You write the songs, you make a record, you go out and you’re instantly a rockstar right? Not necessarily, but we didn’t know that. And it sort of worked out for us that way. FM radio came into fashion and really carried Loggins and Messina to the forefront of college kids’ awareness. Our college tour was very successful and that pretty much launched us.

Tell us about the formation of Loggins and Messina. LOGGINS: Originally we weren’t writing together—I showed up at Jimmy Messina’s house with a guitar and I played him a dozen songs and he liked House at Pooh Corner and Danny’s Song, but he was concerned that what I’d brought him was folk music and he wanted to make a rock n’ roll album. He’d come out of Poco, his second act, and signed a deal with Clive Davis at Columbia Records to be a producer and I was one of the few acts that he initially worked up. I was more malleable than other acts that Jimmy had been sent by Clive to work with. Jimmy was the country of Loggins and Messina, he’s from Texas and brought that sensibility to the group.

And what was it like breaking off as a solo artist? LOGGINS: I didn’t know that it was almost impossible for an act to go solo from a successful duo. Very little history of that happening, Simon and Garfunkel being a good example. Hall and Oates as well—it’s unbelievable that a talent like Daryl Hall could not launch a solo career post his time with John Oates. Because people get used to that name, but I was naive enough to not be too worried about it. Thought that Loggins and Messina was doing great, our intention was to make a record. When I first met Jimmy, his intention was to make a “Kenny Loggins with Jimmy Messina sitting in”, like a jazz record and then launch me into a solo career out of that. So for me, emotionally, I was always ready to go, ‘ok now do I get to make a solo album?’ Then Clive said, “no, you guys have got to stay together for six albums, I’m not gonna release a record of a group that’s already broken up”—so that’s when we became Loggins and Messina and that was a six year deal.

What drove you to have success soon into your solo career? LOGGINS: The duet with Stevie Nicks was really the thing that brought me back into the public eye as a viable artist. I always give her the credit for that, for being generous enough to share her talent and sing that song with me. I got lucky, when I went solo I became the opening act for Fleetwood Mac. And it was through that time of just hanging out and having fun after shows on the road, she said, ‘if you ever need a singer give me a call’ which I was like, ‘absolutely.’ So that was really the thing that launched the solo career.

Starting with “I’m Alright” from Caddyshack and continuing throughout the ‘80s, you became known as the King of the Movie Soundtrack. How does writing for film differ from writing for yourself? LOGGINS: When I write for my own albums, at least from sort of a middle solo career period onwards, they become more and more autobiographical. In order to do that, one has to dig in very deeply to get to those core emotional things that are happening in your life. When you write for a movie, you’re writing for a fictional character or characters. You can transpose your reality onto them, but for the most part you’re safe—your songs are hiding behind other faces and they can do whatever you want them to do. I’m Alright was based on that opening character of Caddyshack, Danny, who’s riding his bicycle through the suburbs and when I first saw the director’s cut of the film, the director had put temp music in, one of which was Gotta Serve Somebody by Bob Dylan. And I just thought, how is this shot of this kid riding his bicycle through suburbia scored by Bob Dylan? That doesn’t make any sense to me. Bob Dylan is like the quintessential rebel and this kid is anything but a rebel, until you get to the end of the movie. Using Bob Dylan at the beginning of the movie was a foreshadowing of what was going to happen so that’s why I went with the lyrics ‘I’m alright, nobody worry about me’ to open—to show that rebel stance of the Danny who isn’t quite there yet.

Is doing so easier than writing for yourself? LOGGINS: I think it’s considerably easier because you can go into an alter ego. For me, the voice that I used on I’m Alright was actually inspired by Stealers Wheel’s Stuck in the Middle with You, which was Gerry Rafferty’s obvious imitation of Bob Dylan and I thought well, heck if Gerry can do it then I can do it too.

You’re the first major rock star to dedicate yourself to writing music for children and for families. Is that inspired by your own family? What kicked that off for you? LOGGINS: Yeah, it was definitely inspired by my own family. I had written House at Pooh Corner that Loggins and Messina recorded when I was a senior in high school, probably 16 or 17. And then years later, my fourth child is on the way and I realized this circle just keeps getting completed, that I was a kid when I wrote that, and my first kids are almost as old as I was. And it was this feeling, like, write a new verse to it and complete the circle. So the idea of the new verse in Return to Pooh Corner is that I'm watching my own child, holding a bear that inspired me to write the first song. So that was the beginning of that idea of making a children's record. Then Don Ienner, who was running Columbia Records at the time, was not pleased with the idea and said, basically, “It'll destroy your career if you do this.” And I said, “No, I don't think so.” I said, “Do you want to hear the music? Because you kind of have to hear the music to get that it's not really a kiddie album.” He said, “No, I'll just take it down the street. It won't count as an album delivered on your contract, but you can make it,” and ended up selling a couple million, so far. And the thing about children's records is they're evergreen. So young couples who are having their first baby are going to be given that album, and it happens a lot.

Did you always want to be a musician? LOGGINS: I look back and think there wasn't anything that was really calling my name passionately, other than that. I never really took it seriously as the thing you do when you grow up until I was in junior college, and then I realized, “I am wasting my time studying things I don't want to do and I should be on the road because rock and roll is a young man's game.” So I quit school and the first offer I got was from a band called The Electric Prunes, which was a psychedelic band in the ‘60s. I toured with them and that was a horrible tour because we were hired to replace the original band by the manager. Only two of the original players were in the band, but we didn't have to play any of their music. So we got to play all our own music. But here you have a psychedelic rock band already with a three album career. So their audience is showing up at shows and you're not doing anything like it. I'm lucky I wasn't tarred and feathered. It was a very rough experience for a young singer-songwriter.

Now that you’re on your final tour, do you have any advice for your younger self? LOGGINS: Yeah, I told my son, my oldest boy, Crosby, when he tried to go on the road and be a solo performer, and he came to me one day and said, “Dad, I don't want your life. I can't do this at 29.” And I said, “Son, if you can quit, you should,” because it's a compulsion. Those who stick with it have got to be so in love with it that they can't do anything else. And I used to tell my son, “Don't have a backup plan. Don't have a plan you fall back on when you decide to do what it is you're going to do. Because you have to have that kind of determination to keep going and get better at what you do and defy the odds.”