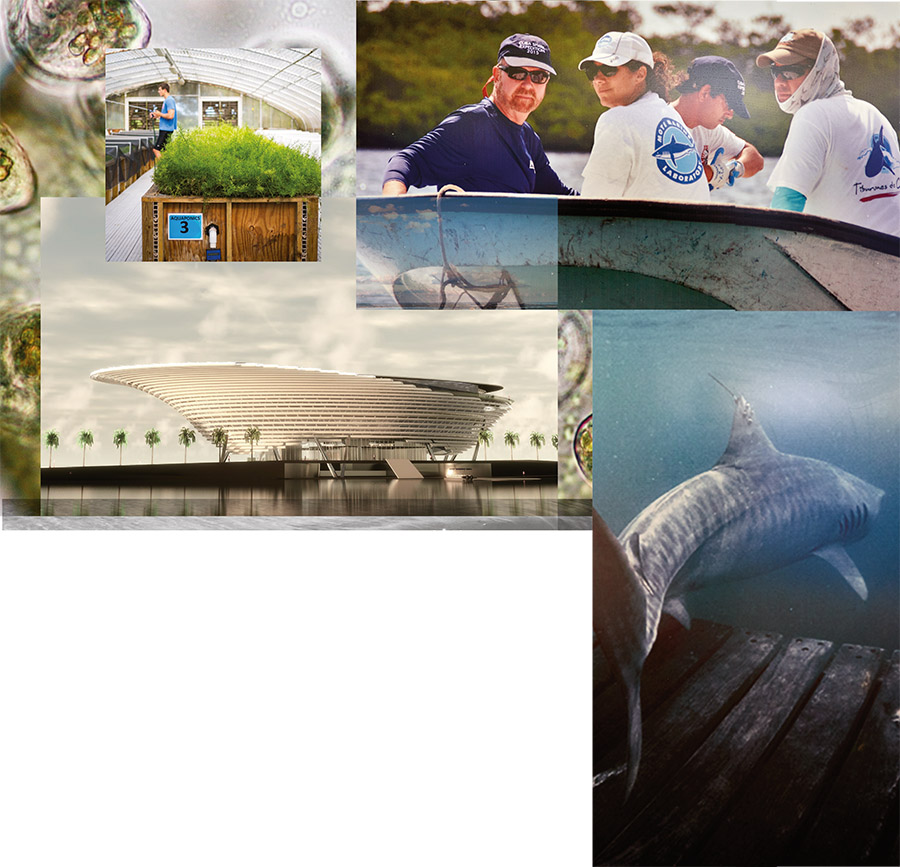

Renderings of a $100-million Mote Science Education Aquarium [SEA] soon inspired gapes and awes. Mote Marine, indeed, was on the move, with plans to cut the ribbon and open a new facility to the public before the end of 2021. “We hope you, all leaders in this community, are supportive friends and members,” Crosby told the crowd, “and will help us, together, to create this vision of oceans for all.”

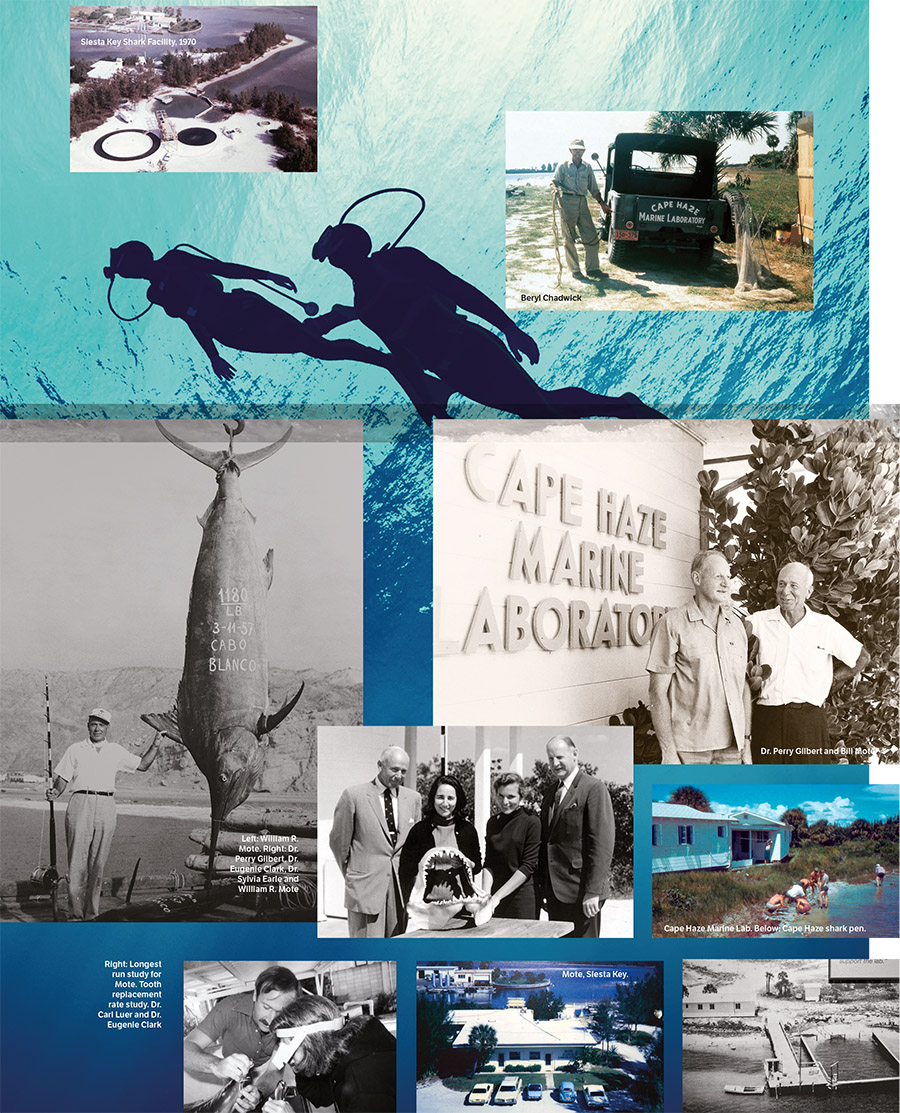

The change in locale marks a major upgrade from the existing aquarium on City Island. But it’s even more dramatic to think of the coming attraction in comparison to the humble Cape Haze facility where the story of Mote Marine began in 1955. That one-room facility in Placida, which doubled as a dock where the wealthy Vanderbilt family could store a boat, existed chiefly so shark researcher Eugenie Clark could quietly—almost secretly—study the migration patterns of sea life in the Gulf of Mexico. More than six decades later, the laboratory continues to provide a foundation for marine and science-based industry in the region.

Humble Beginnings

The true story of Mote Marine Laboratory in many ways begins with the end of World War II. Involvement in the largely European and Asian conflict initially brought to a close many of the scientific research efforts in the United States as industrial resources went toward the war effort. In Florida, two marine facilities in the state focused on the Gulf of Mexico, including the Bass Biological Laboratory in Englewood that operated out of Charlotte County through the 1930s.

According to an official history written by former Mote Marine CEO Kumar Mahadevan, one of the scientists tied to the Bass lab was Clark, an ambitious ichthyologist subverting 1940s gender roles, who found access to a collection of sea-based invertebrates in the Florida laboratory. In archived video for Mote Marine, Clark says she developed her own love of fish and marine life as a little girl, during childhood visits to the New York Aquarium at Battery Park. “I just thought, wouldn’t it be wonderful if I spend the rest of my life studying fish and actually go in water with them and see them underwater?” she said. The scientific field, like nearly every industry in the United States at the time, remained dominated by men, but Clark was willing to explore the globe to chart her own career course. “I don’t want to be anybody’s secretary,” Clark said. “I wanted to do it myself.” And she did. As scientifically minded research in the U.S. wound down, with materials going to build guns and ships and innovation directed toward winning military campaigns, Clark traveled largely conflict-free parts of the world studying sea life.

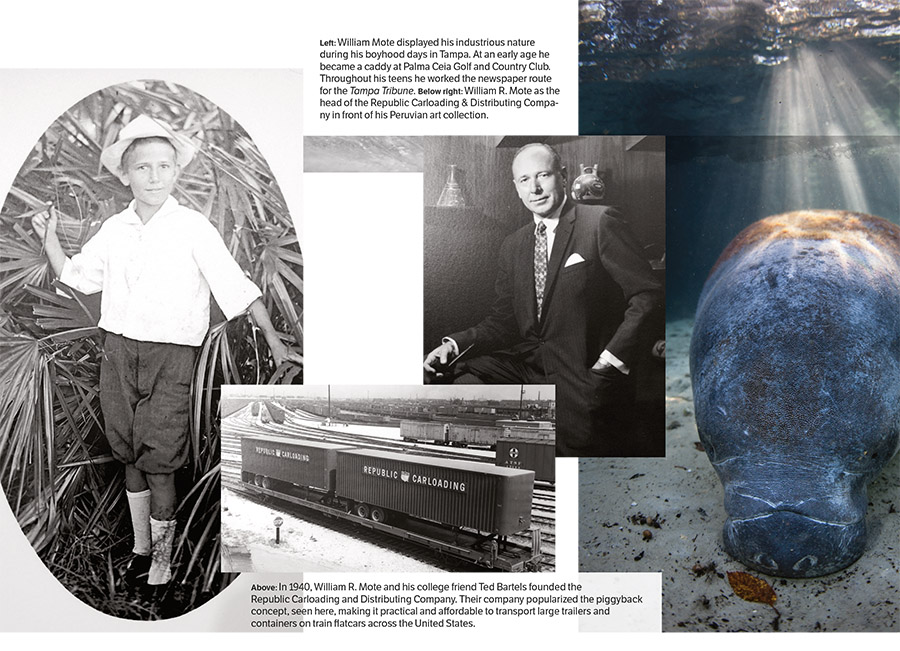

After the war ended, industrial material once again could be directed toward domestic and peaceful pursuits. At the same time, America’s philanthropic class developed a keen interest in funding scientific research. Amid the Space Race and the birth of modern medicine, the wealthy Vanderbilt family looked toward the sea. William Vanderbilt, heir to a rail and shipping fortune and the former governor of Rhode Island, wanted to make his own investment in a brighter tomorrow created by science. His wife Anne, who in the early 1950s developed a fascination with marine research, had a suggestion where the money could go. She’d read a book, the 1953 bestseller Lady With a Spear, written by a female researcher with a small lab in Egypt. That researcher, of course, had been Clark.

The Vanderbilt family owned some 36,000 acres of land on Gasparilla Bay at the time, and when Anne realized Clark’s own ties to marine research in the region before the war, the idea that eventually became Mote Marine Laboratory was born. William set up a meeting with Clark with a proposal. “It’s Anne’s idea,” he told Clark. “She thinks it would be just great if we had a marine lab here. Something like the little one you described in your book.”

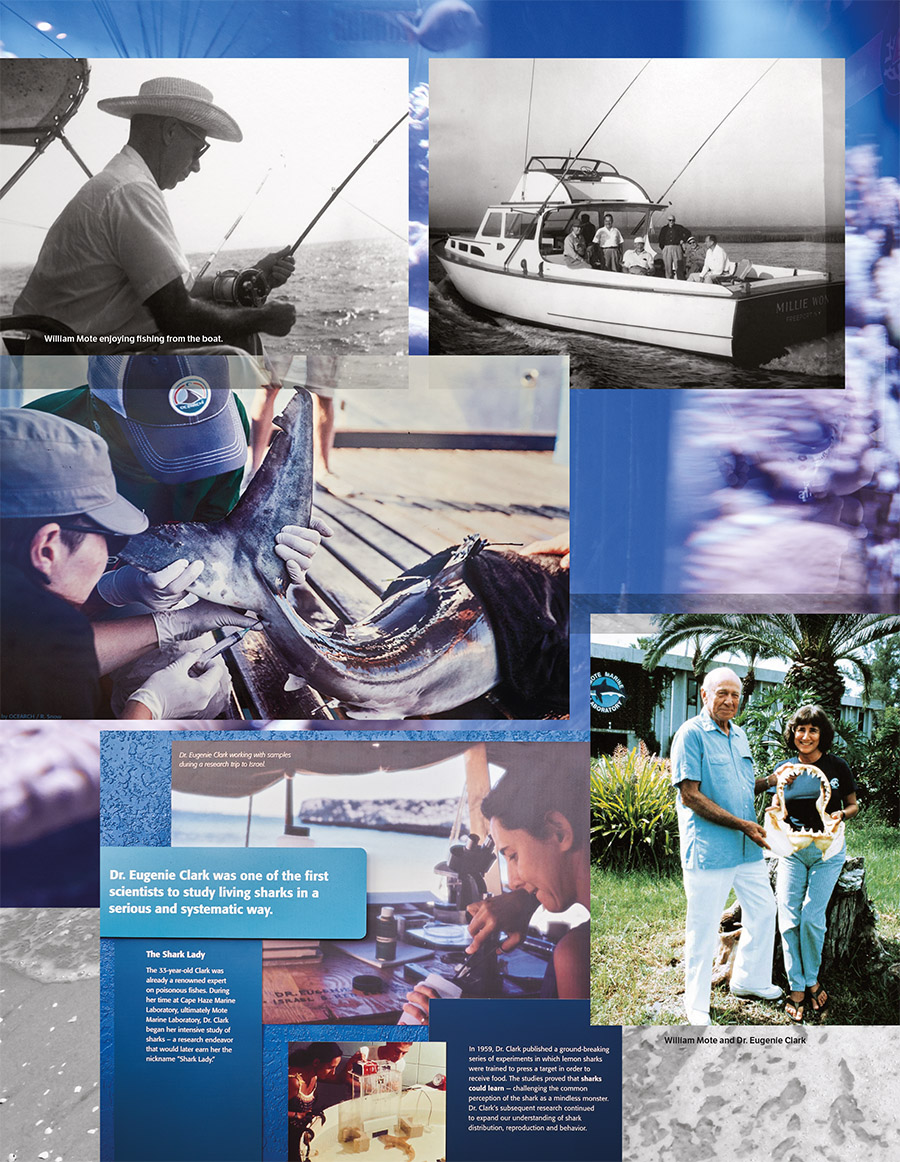

The Cape Haze Marine Laboratory opened in January of 1955 with a $25,000 gift from the family. A one-room building originally equipped with just a sink and a few shelves for specimens, the facility gave Clark all the room she needed to study sharks in the Gulf of Mexico. With the help of local fisherman and the use of the Vanderbilt’s boat, Dancer, she initially conducted research on her own, entering coral reefs in SCUBA gear and crouching among the sharks to study their behavior. In this pre-Jaws era, the large sea creatures didn’t scare the scientist, though she carefully kept still underwater while the beasts swam past.

Perhaps even more important than the way she conducted herself under the sea became how she broadcast the work at Cape Haze on dry land. The laboratory never advertised for scientists to work there, but Clark’s reputation proved powerful enough that some called the facility asking for the chance to work alongside her. By 1960, the Placida lab felt crowded, and, around the same time, Sarasota city and business leaders started to openly seek scientific minds to locate here. Clark’s assistants, tired of living in the wilds of west Charlotte, urged a relocation of the lab to Siesta Key. The growth in reputation also attracted internationally famous researcher Jacques Cousteau to join the advisory board for the lab.But by the mid 1960s, the Vanderbilts’ interest in supporting a Florida laboratory waned, just as outside universities’ interest in Clark grew. In 1966, Clark took a professorship at the University of Maryland, but before leaving Sarasota, she found the lab a new benefactor—William Mote.

Like the Vanderbilts before him, Mote’s fortune came from the transportation industry. The Tampa businessman had been co-owner of Railroad Carloading and had invented a container vessel usable on rail and boat that revolutionized shipping worldwide. He also loved sport fishing, and Clark convinced the Florida native to invest in marine research because of the potential benefits to the hobby. Mote spoke with Clark of a potential plan to buy a huge barge to wander the Gulf of Mexico, equipped so researchers could track sharks on one side of the vessels while he and other fishermen hung bait on the other side. Clark suggested a better use for his money.

In 1967, Mote and sister Elizabeth Mote Rose became the new financial supporters for the lab, which promptly changed its name to Mote Marine Laboratory.

Sarasota Bound

With the Mote family funding research, $200,000 worth of new equipment was installed, including Navy shark tanks still on Siesta Key today. But with Clark gone, the lab entered a period of fluctuating leadership. At first, Clark recruited mentor Charles Breder, who previously ran an American Museum of Natural History field office in Lee County, but after a year he handed the reins to Sylvia Earle, an oceanographer who studied under Clark years earlier at age 19 and later was named by Time magazine as its first “Hero For The Planet.” Neither of those leaders ever wanted a position running Mote Marine on more than an interim basis.

But when Bill Mote took over from William Vanderbilt as board chairman, he sought out permanent leadership for the facility. Through his fishing escapades, he’d met Perry Gilbert, an ichthyologist with a reputation rivaling that of Clark. “He had already written a number of books on sharks,” says Robert Hueter, a Mote Marine scientist who studied under Gilbert. “He was a professorial man with an old school approach.” In 1966, Gilbert earned some national acclaim after being featured in the Don Herbert documentary Attack Patterns of Sharks, which chronicled violent interactions between humans and sharks and showed how sharks track prey sensing vibrations in the water and then pinpoint location based on smell.

As the new CEO for Mote Marine, Gilbert pushed scientists to publish more outside papers. The facility by the time he arrived had grown to span five buildings and the annual budget ballooned to around $200,000. But Mote himself envisioned more taking place. He wanted to transform what still essentially served as a field office for scientists into a major research center. That meant expanding the scope of study beyond sharks, and Gilbert recruited scientists to study microbiology, neurobiology, estuarine ecology and biomedical sciences. Mote Marine researchers began tracking red tide and publishing results. The U.S. Navy hired researchers to develop shark repellants.

Meanwhile, Mote started working with local fishermen to study the local wild populations. Even that seemingly commercial endeavor birthed major scientific projects. For example, a young researcher named Randall Wells in 1970 started tracking native dolphins. “We needed a way to protect the dolphin population from unnatural losses,” he says now, noting how an increase in boating led to greater risk for the native population at the time. But as he started collecting data, he in fact launched groundbreaking research, the significance of which would become clear much later.

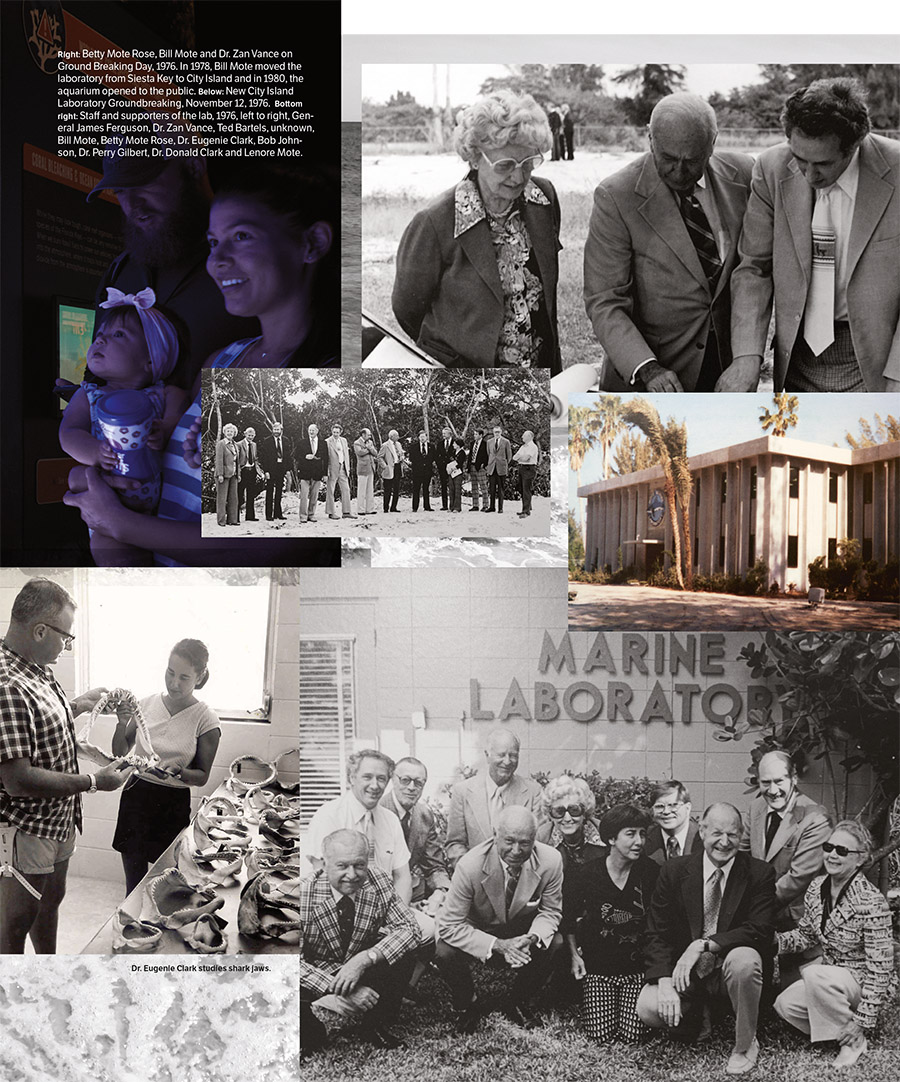

Through most of the 1970s, the programs at Mote Marine remained small by design, even as the reputation of the facility grew. Then in the 1970s, Sarasota City Manager Ken Thompson approached the Siesta-based research facility with a proposal. The Arvida Corporation, which developed Bird Key and owned an excess amount of land on City Island, wanted some type of civic facility there. Sarasota leaders remained as interested as ever in bettering the community’s reputation as a science capital, and a plan came together to offer a facility to Mote on six and a half acres.

Mahadevan, who came onto Mote Marine’s staff as a benthic ecologist in 1978, says the timing proved phenomenal. Mote Marine scientists were starting to run out of space, and Mote had considered relocating everything to property he owned near Charlotte Harbor, not far from where the Cape Haze lab got its start. “But some of the scientists who had been here from the early days did not want to leave Sarasota,” Mahadevan says. “I think they had been very happy to leave Placida and had no interest in going back.” Gilbert heavily recommended Mote look to City Island for an expansion instead. And Mote Marine’s attorney Bob Johnson, a former state representative from Sarasota, offered the same counsel. It was settled. Mote Marine would move further north.

City leaders negotiated a lease to put the laboratory on land owned partially by the city and partly by Arvida, and Mote Marine leaders signed a $1-per-year lease. “Which was pretty expensive at the time,” Mahadevan jokes. Eventually, Arvida sold its two acres of waterfront to Sarasota, and the city remains the sole landlord on Mote Marine’s city island facilities to this day.

Gilbert felt his work as CEO complete after the move and retired from administration, returning to full-time research at the lab. Mote tapped William Taft, director of sponsored research at the University of South Florida, to run More Marine in its new locale. Taft’s greatest contribution came in expanding the grant-winning capabilities at the institution. Bringing coastal ecology into the list of research areas, he installed Mahadevan as the laboratory’s first Environmental Assessment Division director. The laboratory took on a greater role in evaluating the status and health of the Gulf of Mexico. More than $1 million in grant funding was secured for that division alone.

The Original Aquarium

The City Island move also led to the creation of a public exhibition, where for the first time visitors could see some of the specimens from Mote Marine’s research put on broad display. The first Marine Science Center opened in 1980. “I jokingly called it a glorified pet store,” says Mahadevan. “It wasn’t child friendly. Most of the fish tanks were set at eye level for adults.” Still, the inkling of the future Mote Aquarium opened its doors and became stunningly popular. Visitation to Mote Marine, which had been around 800 people in 1967, leapt to nearly 17,000. And the lab in the 1980s continued to land bigger projects. The Florida Power Corporation in 1980 sponsored a $2.3-million study on the impact of a coastal power station on the natural life in a nearby estuary. By 1983, Mote Marine started its own soft money foundation to help fund research in addition to grants. Mahadevan credits the institution’s second financier with the vision to expand the laboratory. “If Bill Mote didn’t want it to grow, it would have stopped,” the scientist says.

But for a long time, the benefactor worried whether the broader community shared his same commitment to the facility. That led to an insular board of directors made up of Mote’s friends and family. After winning such support from the city, Johnson encouraged Mote to look beyond his inner circle and bring in more community voices. In 1986, he even allowed Johnson, at the time a state senator, to take over as chairman of the board, only the second time the gavel had passed in the institution’s history.

When Taft retired in 1985, Mahadevan and fellow researcher Richard Pierce served together as interim directors of the lab just long enough to hire a new director, Robert Dunn. But Dunn left after a year to pursue other interests, and staff at Mote Marine pressed Mahadevan to take on the CEO role permanently. He held that position from 1986 until 2013. While he says he took on the position reluctantly, he tackled the post with aplomb. In 1988, he approached Mote about finally getting serious about its public facilities. Sick of the “pet store,” he said the laboratory needed a full-fledged aquarium.

At the time, a couple nursing sharks in a small tank at the science center offered visitors the only glimpse into the ichthyology that earned Mote Marine a national reputation. Sharks served as the logo for the lab. Why not install real tanks and give a reason for members of the public to drive out to City Island?

The aquarium opened in 1988 and ever since has served as Mote Marine’s publicity machine and unwitting disguise. Interior Design Judy Graham recalls when her friend Dan Miller, later the region’s congressman, encouraged her to take a tour of Mote Marine, and until then, she had no idea the amount of science being done on City Island. A dozen scientists filled one building, while the aquarium largely entertained guests next door.

But Mahadevan says the large tanks installed for the aquarium also allowed for an expansion in research. When Mote Marine made space for manatees, Hugh and Buffett came to the aquarium in 1998 to participate in an animal husbandry research project and for display. The popularity of the sea cows—perhaps the world’s most famous manatees following the 2017 death of Snooty—proved so great the beasts became permanent residents at Mote Marine.

And the institution along the way grew its own talent. Hueter came to Mote Marine Laboratory as a post-doctorate resident in 1988, mostly because the laboratory lineage included Clark and Gilbert. “I knew within the first month or two that this was the place I wanted to build my career,” he says. In coming years, he would be one of the first scientists in the world to show that sharks, once thought of as aimless predators in the sea, returned to native grounds later in life for breeding, the same as salmon go to home streams to spawn and sea turtles travel back to the nesting grounds where they were born when it comes time to lay eggs.

Wells, meanwhile, continued his dolphin research at Mote Marine, which moved from the facilities on South Siesta to the shores of City Island when the laboratory made its move. In 1989, Wells showed the 19 years of research so far on the Sarasota Bay dolphin population to the Chicago Zoological Society, which started funding continuous research that continues today. Wells’ 48-year-old study now stands as the longest running observation of a wild dolphin population anywhere in the world, and reported last year a record number of dolphin births occurred in the waters. The program both helped nurse injured dolphins to health and kept tabs on Nicklo, the oldest known dolphin in the world.

Meanwhile, scientist Carl Luer began research seeking to discover new cancer treatments from a study of sharks, building off the work of Gilbert in the field. Mote Marine opened a fishery at Port Manatee and started to expand physical facilities on City Island. Bob Hallard, the sea researcher who discovered the wreck of the Titanic, asked Mote Marine scientists in 1993 to participate in an education project documenting Mediterranean Sea wrecks in a way school children could explore them. The potential of Mote Marine exploded under Mahadevan’s leadership. By the year 1999, the operating budget grew past $10 million for the first time.

Reputation Bloom & Global Impact

The reach of Mote Marine expanded beyond Sarasota as well. In 1994, the Pigeon Key Foundation encouraged the Sarasota laboratory to open a campus in South Florida to study life in the coral reefs there. That same year, the White House sent officials to dedicate a federal research facility there, though a hurricane would wipe it out four years later and Mote Marine had to start over again in 1998. Hueter notes that a Mote Marine-led study of rays in the Keys resulted in the population being placed on the U.S. Endangered Species list, a first for a fully marine animal.

Mote Marine leaders also opened up a new facility in Charlotte Harbor, long a desire of Mote himself, and the laboratory launched field offices in places like Pine Island in Lee County. An aquaculture park opened in east Sarasota County that started raising commercial caviar, some of which got served at then-Gov. Charlie Crist’s wedding in 2008. By the year 2010, Mote Marine boasted five campuses in operation.

The reputation for science grew larger, but Crosby, who joined the Mote Marine staff as senior vice president for research in early 2010, said its reputation for nurturing talent remained just as vital. He left a position in Hawaii to move to Sarasota, citing the family atmosphere of the lab for encouraging his move. “I found when I came here for my initial interview that they had an amazing culture at Mote,” he says. “It’s one I can only describe as one of Ohana, or of family.”

Through all its iterations, Mote Marine remained nimble and entrepreneurial. As an independent institution, scientists must scrap for grants to pay their own salary, something Hueter acknowledges can generate stress but also freedom. It also helped Mote Marine in a 2010 transition from a well-respected institution to one holding critical knowledge about a natural disaster. Crosby certainly didn’t anticipate that a month after his arrival in Sarasota an oil rig would explode in the Gulf of Mexico. The Deepwater Horizon disaster killed 11 people in April 2010 and cracked open a hole in the ocean floor. Over a period of about two months, some 210 million gallons of crude oil leaked into the sea, threatening shorelines from Louisiana to Florida.

“I don’t call it a spill,” Hueter says. “I call it a blowout.” The potential damage seemed hard to fathom—or even to measure. In fact, scientists at Mote Marine Laboratory realized quickly they hardly knew what to measure damage against. So they decided to figure that out first.

“I watched with awe at the ability to marshal all of our resources to get out there immediately and start measuring the impact,” Crosby says. Mote Marine scientists gathered data to form baseline measurements on water quality and documented the travel patterns of indigenous species. An aquatic robot started traversing the surface of the water to keep track of where the oil plumes headed in the currents.

Mote Marine became the number one source of information on the oil spill’s impact in the country. It’s something Mahadevan does not believe any government-run institution or university could have achieved on such short notice. Scientists found that sharks started to deviate from migration channels utilized for years. And while the oil slick never did reach Southwest Florida’s shoreline, Mote Marine officials have been able to document subtle impacts of the ecological disaster.

It’s not the only place Mote Marine showed national leadership. Starting in 2003, scientists there began a relationship with counterparts in Cuba, and the Sarasota institution remains one of the only American entities to have a working relationship with the nation, one that has endured through shifting foreign relations situations in the Obama and Trump administrations; Hueter is preparing for a trip to meet with scientists in Havana later this year. It’s part of a significant legacy for Hueter, who started under the tutelage of Gilbert, developed a working relationship with Clark (who retired to Sarasota and returned to Mote Marine as a senior scientist) and has now started to wonder how his own legacy fits into the history of the institution.

After decades in charge of Mote Marine, Mahadevan had overseen its evolution from a well-regarded small lab to a regional attraction and then into an international powerhouse. But with a tenure that stretched across the turn of a millennium, he decided to hang up the director’s coat himself in 2013. That’s when he let Crosby in on another long-term project in the works—a leadership transition.

Mahadevan told Crosby that he’d in fact been looking for a potential successor back when Crosby first interviewed in Sarasota three years earlier. Now, he wanted to have more time with the wife he married on the Mote Marine campus, and to track his growing number of grandchildren instead of grant opportunities.

Future Vision

Crosby, officially the ninth CEO but blessed and cursed with the task of following its longest-serving leader, now stands ready to bring Mote Marine into another age. Already, he’s helped open a second small aquarium, this one in the Florida Keys near a satellite campus there. But the announcement of Mote SEA at Nathan Benderson Park will be a monumental task on a different level, much larger in scope than the opening of the existing City Island aquarium in 1988.

It’s been a controversial move. Sarasota City Commissioner Hagen Brody heavily criticized Mote Marine’s intentions to leave the city after enjoying a $1-a-year lease for decades. But Crosby stresses Mote Marine Laboratory is not going anywhere. Moving its main aquarium to a place closer to Interstate-75 will allow scientists to once again take over the existing buildings on City Island for research. The display tanks, large enough to hold an array of aquatic life, will be used again for research. Mote Marine today houses 24 separate research projects, and plans call for the recruitment of more PhD scientists in the next several years. “It’s an amazingly diverse institution,” he says. From cancer therapy to aquaculture, the laboratory remains on the bleeding edge of expanding human knowledge.

The new aquarium certainly marks a shift, and it’s one forcing a degree of introspection. “Scientific research has always been our primary mission, and now that may change over to education,” Hueter says. But he welcomes that change, knowing full well how the Mote Marine reputation could grow in the public eye once the new aquarium opens in 2021.

Graham, now a member of Mote Marine’s board for 30 years, today guides a $50-million fundraising campaign, the largest in Mote’s history. The new capital will be on top of some $52 million already in pocket, and it still won’t cover all costs. In total, opening a new aquarium should run about $120 million, officials estimate. But once it’s up and running, Mote SEA will serve as a regional attraction more in line with major aquariums in Tampa, Atlanta and Chattanooga, Tennessee.

“This is what Mote needed to do to attract, nurture and keep that next generation of the brightest minds in marine science,” Crosby says. “We need to expand our current scientific core, and the only way to do that is to expand our education program.” In many ways, it’s a mission not altogether dissimilar from the dreams of post-war industrialists like the Vanderbilts, who invested in science as a path to a better future for all of society.

And based on Mote Marine’s track record so far, the work here will continue to hold the attention of the scientific community.

Most of the original players who brought the Cape Haze Marine Laboratory online and later turned Mote Marine into an international institution will never step foot in a new aquarium. William Vanderbilt died in 1981. William Mote died in 2000, as did Perry Gilbert. Clark, the Shark Lady who started it all, passed away in 2015. Every one of those individuals would be commemorated with obituaries in the New York Times. Clark’s death inspired tributes from scientists around the world and a feature in National Geographic, a publication she wrote multiple stories for throughout her career.

So what will succeeding generations remember about Mote Marine’s current leadership? Will the new aquarium prove as transformative as that pet store of an exhibit space in 1980? Will researchers working in a challenging grant environment and increasingly relying on philanthropy ahead of government funding continue to make as many groundbreaking discoveries? Crosby and Mote Marine’s existing team of scientists are anxious to see.