Any kindergartener can scribble lines on a page but Florida lawmakers have spent close to half a decade and still haven’t gotten the redistricting process down. To be fair, these lines end up suffering far greater scrutiny than the works of art found on a typical refrigerator, but the drawn-out process has left Southwest Florida divvied in a way that leaves political leaders in the area wondering about the region’s position over the next five years.

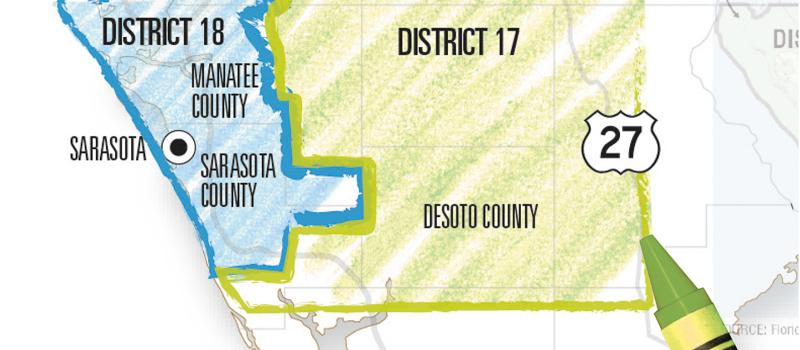

A new map of Florida’s Congressional districts approved in December by the Florida Supreme Court divides Sarasota County into two districts, moving the geographic and population center of the district held by U.S. Rep. Vern Buchanan, R-Sarasota, closer to Bradenton than Sarasota. Meanwhile, Venice and North Port voters will now be in the district held by U.S. Rep. Tom Rooney, R-Punta Gorda. It’s a change that gives more representation in Congress than Sarasota County has enjoyed for years, but also one that puts voters in the county on the outer edges of their district. Manatee County voters, of course, are in a different situation, and it may be more likely than ever that a congressman representing that area could have their main office in Manatee.

But as the details were finalized in the Congressional battle, a separate fight was being waged regarding Florida’s state Senate districts, and somehow that effort seemed at one point destined for a similar end, dividing northern and southern Sarasota County into separate Senate districts. Not until the end of 2015 did voters learn the county would be kept in a single Senate district.

So how did it reach this point? A series of constitutional amendments, special legislative sessions and extended court trials weave a path almost as convoluted as a drive through U.S. Rep. Corrine Brown’s Congressional district and ends in a place that leaves more people than normal unhappy in Southwest Florida’s political circles.

Playing Fair

Any political observers old enough to remember reapportionment efforts in past decades know the process has always been controversial. Redistricting exposes perhaps the most blatant sausage-making ugliness Tallahassee ever endures. And along the way, accusations of racial gerrymandering and partisan stacking of the deck grew loud. As technology allowed for greater data mining and digital construction of maps, the ability of lawmakers to draw districts favoring political parties—or even individual constituencies—grew. All of it prompted activists to gather petitions and place the Fair Districts amendment on the 2010 statewide ballot, and more than 62 percent of Florida voters approved the requirement that the next time districts were drawn, lawmakers could not do so in a way that divided communities for the purpose of favoring a party or incumbent office holder, among other strict rules. “This is a thrilling victory for the people of Florida and for the open, fair and accountable government,” said Dirdre McNab, then-chair of the Florida League of Women Voters.

But among members of the Florida Legislature, the development was not applauded. State Sen. Mike Bennett, then president pro tempore of the state Senate and now Manatee County Supervisor of Elections, said it would be nearly impossible to comply with the restrictions. “This is going to end up in court,” he told SRQ at the time. And while lawmakers spent much of the next two years holding careful public hearings, and even having a Republican-controlled Legislature approve a map that resulted in a greater percentage of Democrats representing Florida in Washington, court is exactly where the process has ended up. The maps approved by lawmakers and signed into law by Gov. Rick Scott were legally challenged, and while the map for Florida’s 120 state House districts has been allowed to stand, the districts for the 40 state Senate districts and 27 Congressional districts was rejected by Judge Terry Lewis.

Through the summer of 2014, the Legislature again grappled with the process, but that resulted only in squabbles between the House and Senate that proved impossible to resolve; among the key differences, Florida Senate leaders favored a map that did not split Sarasota County into two districts, while the House forwarded a map that divided it. The Congressional maps that came from Tallahassee were again tossed by Lewis, who instead approved a map drawn by the League of Women Voters. That map became law on Dec. 2 when the Florida Supreme Court signed off on her decision.

Sarasota Frustrations

Democrats, a minority in the Legislature, generally lauded Lewis at the statewide level, but party leaders on both sides in Sarasota County have expressed frustration at the final Congressional map, which will put Sarasota city voters in the same Congressional district as those in South Hillsborough and North Port voters as co-constituents with residents of Okeechobee County. The district represented by Buchanan, who opposed dividing Sarasota County, extends through all of Manatee County and into Hillsborough County as far as Adamsville.

But party leaders, responsible for recruiting candidates to run this fall expect the lines set by Lewis are the ones that will exist until the Legislature goes through reapportionment again in 2022. “I think Sarasota County is much better off having one representative,” said Joe Gruters, chairman of the Republican Party of Sarasota. On that much, he and Christine Jennings, chairman of the Sarasota Democratic Party, are in agreement. “We wish this was not the case,” Jennings said. “We wish Sarasota County was kept whole.”

For 2016, no national experts are placing Buchanan or Rooney on endangered lists, and local pundits don’t expect turmoil this year. “Buchanan can stay as long as he wants,” says New College of Florida associate professor Frank Alcock. But how long that will be? Buchanan, current co-chair for the Florida Congressional Delegation and one of the wealthiest members of the U.S. House, has considered running for Governor or Senator and never shied away from making those ambitions known.

More immediately, though, the a local state Senate district has been creating far more speculation and could still change before candidates qualify to run.

Who Follows Detert

State Sen. Nancy Detert, R-Venice, in October announced her candidacy for Sarasota County Commission for 2016. That means when her seat comes up for election this year, there will be no incumbent, and that’s just the sort of thing that gets ambitions high within the political class. The opportunity to succeed Detert has drawn big political names into play, but the redistricting process also presented the potential to knock candidates out of the running.

To date, no Democrats have thrown their hat in the ring, though at press time Jennings expected a candidate to imminently announce. The Republican field, meanwhilw, has been rich with candidates. State Rep. Greg Steube, R-Bradenton, has eyed the district, and while technically filed to run for re-election to the state House, he has raised more than $194,000 with the stated ambition of Senate in mind. Meanwhile, former state Sen. Doug Holder, R-Siesta Key, has filed for the Senate race and raised more than $152,000. Former Sarasota County Commissioner Nora Patterson, the most recent entry into the race, has pulled together more than $110,000 for a run, including a $40,000 loan, for the seat as well.

But it looked shaky through much of 2015 who would be eligible for the seat. A map coming out of the Florida Legislature, but notably without the support of a majority of state senators, would have pushed Steube and Patterson out of the race. Beyond the ambitions of these individuals, though, political leaders through the region were flustered that Sarasota County would once again be divided into two districts, with Venice and North Port voters suddenly separated from north Sarasota and potentially represented by a senator living as far away as Okeechobee County. The potential led Detert to vote against the map on the floor of the state Senate, one of eight Republicans in the chamber to do so. “I don’t even know how I can explain this back home,” she said on the Senate floor.

As it turns out, she wouldn’t have to for long. Circuit Court Judge George Reynolds on Jan. 30 threw out the map, deeming it too partisan, drawn to favor Republicans. But in Sarasota County political observers of all stripes were thrilled by the move. “In our case, the judge chose the right map,” Detert says.

For all the wrangling, Detert’s district ended up looking almost identical to the way it looked the last time Detert ran. The district includes all of Sarasota County and parts of northwest Charlotte County. Instead, it was state Sen. Bill Galvano, R-Bradenton, who will have to run this year in a sweeping district that used to include most of Manatee County and part of south Hillsborough County while then sprawling eastward into all of Hardee, DeSoto and Glades counties and the southern half of Highlands County. Under the new lines, his district includes all of Manatee, southeast Hillsborough County and a small part of south Pinellas County. But Galvano, in line to become Senate President in two years, is favored to win through the 2020 elections. After that point, the Legislature is tasked once again with redistricting for all chambers.

In the race to succeed Detert, reactions covered a range of thoughts among candidates. Steube, Patterson and Holder all praised the choice to keep Sarasota whole, though neither Holder nor Steube had much good to say about the court challenges. “I anticipated the courts would go with a plaintiff’s map, and they did so,” Steube says. As he has raised money for his House seat, he has made clear all along he will transfer the money to a Senate campaign if the opportunity arises, and the new lines allow him to do just that.

Patterson was pleased the process ended as it did, not with the divides created in the Congressional map. Voters in south Sarasota County were especially hurt, she says, by the potential of being cut off from Sarasota. “That really made a lot of people unhappy, both psychologically for being severed from the rest of the county and practically in terms of hurting our ability to influence the world,” Patterson says.

Holder, who could have benefitted by being the last prominent candidate living inside a district, says he is still glad to see the county kept in one Senate district. But on a statewide level, he doesn’t care for the court-selected redistricting plan, one that will make several safe Republican seats more competitive. “Looking at it from a statewide perspective and from a Republican Party perspective, it is not ideal,” he says. “It has been pretty detrimental to the people of Florida having this play out in the courts. I don’t think it was a comfortable thing to watch.”

Detert feels the same way, and still feels the map drawn by the Legislature in 2002 was a solid product. “I served on the committee that drew that map in 2012, and there was not a thing a matter with it,” she said. “The League of Women Voters, the Democrats and the ACLU put us through a painful exercise for pretty much no good reason.”

Until a final map was drawn, Florida Democratic Party executive director Scott Arceneaux told SRQ he has discouraged any Democrats from filing for state Senate. Jennings expects an announcement soon, and that likely means this race will prove interesting through November.

Of course, Steube notes that, even now, uncertainty remains. The Florida Senate could appeal Reynolds’ ruling. If that happens, the map will continue to be a point of speculation straight into mid-March.