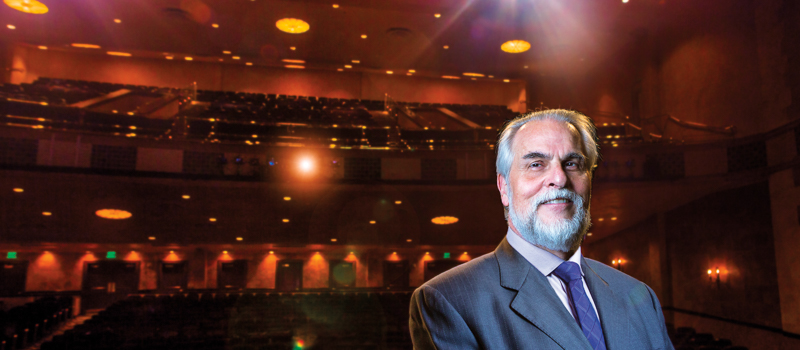

After 28 years, more than 30 operas and nigh countless concerts and musical performances,Sarasota Opera stands poised this month to become the only opera company in the world to perform the catalog of esteemed Italian composer and dramatist Giuseppe Verdi in its absolute entirety, down to the last note. Closing out with the premieres of two of Verdi’s grandest and most popular operas, Aida and The Battle of Legnano, both shows will end their respective runs on the Sarasota stage this month at the climax of “Verdi Festival Week,” alongside two concerts of Verdi’s non-operatic compositions, an international Verdi Conference with scholars from across the globe and a retrospective exhibit on what came to be known as “The Verdi Cycle.” It’s a feat attempted before, by storied companies such as London’s Covent Garden and the San Diego Opera, but none have yet succeeded. “And, it’s a project that was never meant to go on as long as it did,” says Maestro Victor DeRenzi with a bit of wry humor. Between recession-related setbacks and necessary structural renovations at the opera house, the Cycle has run longer than initially expected and DeRenzi is excited to have completion in sight. As conductor for the company, DeRenzi will make history this month as well as becoming the only person in the world to have conducted every note Verdi wrote.

And each note is worth it, according to DeRenzi, who will freely refer to Verdi in conversation as one of the world’s greatest dramatists; a writer, composer and teller of tales who understood the human condition “in a way that maybe only Shakespeare got close.” Verdi captured the essential nature of human drama – the choice and the consequence, the play and pull of duty and desire. “But what’s great about Verdi,” says DeRenzi, “is he never judges those characters, just presents them.” The audience must internalize and engage, allowing themselves to be changed. This, he says, is the difference between art and entertainment, the ineffable magic of Verdi that served to capture this community.

“It was all because of the audience response,” says Executive Director Richard Russell. Previously a performer with the company, Russell sang in what would become the first show of the Verdi Cycle, a 1989 production of the popular Rigoletto. The next season, DeRenzi followed Rigoletto with the rarely performed Aroldo, where audience reaction “surprised us all,” says Russell, despite the opera’s relatively obscure status. In 1992, the company pushed the audience further, performing both versions of Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra in one season and still meeting packed houses and enthusiastic applause. Four years after Rigoletto, the company announced its intention to produce each of Verdi’s operas, expanding to include every note in the following year. “By the mid-‘90s, this following had begun,” estimates Russell, and the project officially became known as The Verdi Cycle.Writing prolifically from the 1820s to the 1890s, Verdi left behind a massive amount of musical material, and working with Verdi scholars around the world and at organizations such as the American Institute for Verdi Studies and the Italian National Institute for Verdi Studies, DeRenzi has spent more than two decades tracking it all down. Some has only been made possible through the growth of the internet and increasing digitization of records. Throughout the Cycle’s duration, the company has revived many pieces not played in decades or even more than a century, breathing life into works ignored with premieres and celebrations. His great musical pilgrimage nearing its completion, DeRenzi retains a special place for it all. “Art is what makes us different from animals,” he says. “You can live in a cave, but once you put something on that wall, you’re not an animal.”

Saving the biggest productions for the finale, Aida and The Battle of Legnano make a fitting tribute both to Verdi and the company, which weathered the recession in form to renovate its orchestra pit and accommodate the closing operas in style. “It just serves to underline what a special community this is,” Russell says. Through thick and thin, the company’s committed donors remained, even if ticket sales waned. A retrospective exhibit entitled Verdi In Sarasota, hosted in the Sarasota Opera library, commemorates this journey, exploring the many facets of operatic production, including the intricate and lavish worlds of set and costume design. Continuing the educational theme, the company will host an international conference in partnership with the American Institute for Verdi Studies, featuring visiting scholars and experts in a free and open discussion about the man and his music.

Verdi Festival Week concludes with the latter of two concerts bookending the celebration and Verdi himself. The first showcases Verdi’s youthful output, incorporating compositions written prior to his first opera, including music DeRenzi estimates has likely not been heard since the 1820s. The latter presents some of Verdi’s final work including the Te Deum. Bringing his own personal journey full circle, Russell will join the chorus onstage for this final show. “To be here at the completion is really quite moving,” says Russell, with DeRenzi echoing, “It’s a completion of something, but not the finishing of something.”