Astronauts study outer space and celestial bodies within it. While arborists specialize in surgical care for individual trees, Arbornauts are a species all their own. Dr. Margaret Lowman, aka “Canopy Meg” of the Tree Research, Education and Exploration (TREE) Foundation, is an arbornaut. There aren’t many out there in the world to descend and share their experiences. We convinced Canopy Meg to take a break up there—surrendering her sandwich to an angry troop of monkeys (yes, they threw branches at her) and dodging flying snakes (yes, they exist outside your nightmares)—and bring her boots to dirt to chat with us about her unconventional career as a woman biologist and botanist.

From Samoa, Malaysia and West Africa to Peru, Panama, India and Biosphere 2 in Arizona, her work has taken her all around the globe to science research facilities as the only female in the lab, to international conventions speaking in front of an audience exclusively made up of men and to the tippy tops of trees completely alone with nature. Nicknamed the “Real-Life Lorax” by National Geographic, Canopy Meg duly earns her pseudonyms—hanging from the metaphorical frame of an umbrella that many of us only hold the bottom handle of. With every ascend, she defies gravity with undying trust in century-old branches, her harness and climbing rope, all the while sharing oxygen with neon bugs, rare reptiles, exotic birds and leafage most of us landwalkers have yet to lay our eyes on or have any inclination exist. In a candid Q&A with SRQ, Meg gives us a peak (pun intended) into the life of an arbornaut and author—suspended in the sky and exploring the unforeseen flora and fauna of the treetops as if they belong to an atmospheric layer all their own. Or, as she likes to call it, “the eighth continent above us.”

SRQ: How would you describe arboriculture? Can you expound on all the different professional gigs of tree climbers?

Margaret “Canopy Meg” Lowman: There are a couple of ways to tackle the tops of trees professionally. Technically, I’m an arbornaut—an explorer of the treetops—which links to the discovery and the science. I have plenty of colleagues and I’ve done a lot of talks at international conferences for arborists. An arborist is that person that comes in and trims the dead branch of a tree hanging over your house, or maybe prunes back a tree downtown because it’s starting to grow over the road. And that’s a very technical skill where you hope that person has respect for the overall shape of the tree and the future health of the tree. In a way, we work arm in arm because we both use harnesses, we use ropes to get up the trees. But my work is a lot more delicate—I don’t want to disrupt or disturb the branches. They go up with some pretty hard, tough hardware like chain saws. Then you have the ultimate logging industry, which is a whole different, but important, group because we need safe, sustainable timber. And then there are specialty groups—now we have tree house builders. I just spoke at the World Treehouse Conference last year in Oregon. It was so cool. Ninety-nine percent guys—300 of them all over the world that build tree houses. So a whole other profession is being spawned from the interest and excitement of treetops.

Could you tell us about your upcoming book release, The Arbornaut: A Life Discovering the Eighth Continent in the Trees Above Us? What inspired you to write this?

This book is a labor of love because I wanted to write a memoir that talked about my, what I call, misadventures in hopes that other girls and women in careers, and especially women juggling family and career, might learn from my experiences. It starts with my childhood and hopes that kids will learn that even the most ordinary kid can make a new discovery. I was totally ordinary growing up in a very rural town. You just never know. You might just have to climb a tree.

How do you describe this eighth continent? What is the significance of seeing the rain forest canopy as a continent of its own?

As I look back on my career, I wanted to climb trees to study leaves. I was a little kid that loved fall foliage growing up in New England. In college, I realized it would be a really easy thesis to do in the tropical rain forest because they’re always green and they never turned red and yellow and fell off the tree. And so I thought, “What’s going on up there?” Well, when I got up the tree finally, after making a slingshot and sewing a harness and doing a lot of crazy things as a graduate student, things were up there. I was in the middle of all these swarms of insects and birds eating the insects and lizards. What I realized is here’s this, what I called affectionately, the eighth continent—and so did a couple other biologists independently—meaning it’s like a whole new world. It would be like going to Antarctica for the first time. Or maybe when Columbus came to South America for the first time to see this amazing country that’s right above our heads. But until 1979, when I went up there and a couple others, nobody ever knew it existed. So, hence the term “eighth continent.”

Over the years, you’re written many books (It’s a Jungle Up There, Forest Canopies, Life in the Treetops, Muddy Boots), how was this one different from the others?

Most of my books to date have been with academic publishers, which is what scientists usually do. They don’t have to, but in my case, I kind of created a new science, which was the science of the tree, top biology or canopy biology. It was incumbent upon me to, say, write the textbooks, write the methods, public science books, write up the proceedings of some conferences over the years. Life in the Treetops is a bit of a memoir, but very early in my career. What were those things that I really I struggled with as a very young woman scientist with insecurities and no confidence, a single mom raising two kids. That actually did really well. It even got a cover in the New York Times book review. So I totally lucked out. Then It’s a Jungle Up There: More Tales from the Treetops, follows my adventures with my two boys—because they came with me everywhere. If I left them at home, I would’ve been arrested. Right? So they came on a lot of my trips and they wrote journals—that was their assignment usually. So we pulled those together into a very fun book about a mom’s view in one rain forest and then the boys’ perspective in that same forest. But now I’m really approaching, you know, the senior years of my career. So I can’t only talk about those early days, but I can talk about how I did reinvent my field to mentor more minority students, to save more rain forests, to do things that really are for the global good.

Is that the story you wanted to tell in The Arbornaut?

I wanted very much to kind of illustrate how in any career, and especially conservation biology right now, we have a responsibility to try to turn our profession into something that will make a difference for our kids. And that’s I think why a memoir at this age, before I’m in my grave, but when I’m maybe in the final chapters of my career, it’s a good time to comment on these types of things and be a little bold. I will say, the Me Too generation, the whole movement, allowed me to say things I was way too scared to say 20 years ago. And my field is rife with problems. Camping in the middle of the Amazon on an expedition with 30 men and there’s no one else within a thousand square kilometers, you can imagine there’s a little bit of risk. Field biology is full of hurdles for women and hurdles for minorities. I think the best success for them is if people like me and my good friend and marine explorer, Sylvia Earl, and others speak out and say, “Hey girls, this is how it was. We can, we will support you to do better.” And I’m excited about that—I think it’s a good time to make sure people have a better voice than I sure did it when I was a young professional.

How was the process of writing the book? Did sharing your life’s story come easily? What were the challenges of capturing your world within the pages?

It was a bigger challenge than I expected. I was very fortunate that I have a great literary agent and she put this book out to bid. So I may never have written it if it hadn’t been for her encouragement and kind of steering me in a way; I didn’t quite understand the whole process. So once my publisher, Macmillan, had the winning bid, suddenly there I was thinking, “Oh my gosh, I’ve got to think about what I’m going to write.” I’ve been a hermit for two years, sitting alone and thinking about my childhood. I called my kindergarten girlfriends and we’re still best friends. I contacted my academic adviser in Australia and had them help me re-create some of the stories with colleagues that I had remembered to get the sense of detail, because the one thing that the publishers wanted was immersion in the story: Were you scared when you first climbed a tree? How did you make a slingshot? How did you make a harness on a seat belt webbing? What kind of sewing machine did you use? How many bugs bit you in the tree? I had to go like, “Holy cow, these are amazing details.” I had to really reach back in a kind of recall process. And that was pretty fun. I’m happy to say, I passed the dementia spectrum so far. I’ve been very lucky to have wonderful old friends and runs around the world that I could reconnect with to relive some of it, an amazing jog of memory.

The international Marie Selby Botanical Gardens orchid event from 2003 must have been an incredibly difficult time for you—ultimately ending with your departure as Selby Gardens’ executive director. What are your feelings now about that chapter in your life—do you feel it had anything to do with your gender?

I do recall that, because we did have a strong, maybe overly macho male board chair and we had some issues with all-male orchid biologists. The things that went on, that as I reflect back, still occur to women in different countries today. As you can imagine, I work in African countries and I work in India and they still have those ratios. At different levels, the woman might still be making the coffee or she might have to take the hit for what the guys did. And I feel like that’s a pretty important issue in scientific communities; it still remains a really big case study for a lot of women leaders. If anything, I can strongly say the fallout at Selby actually helped my career because it showed that women can walk away when they are the only woman in the room and they can remain strong and they can achieve plenty of things, but they should not remain under the suffocation of people like a bad male board chair or, you know, issues where you can’t be productive. And I think that’s the message for women or many different minorities that at some point you have to look at how and where you can find that environment to be productive. That’s really, really important.

With more support to speak up now more than ever, do you finally feel you can share your challenging experiences and reflections of that event in your recent book, The Arbornaut?

I do touch on it. I kind of call it “breaking the glass canopy,” where there were a lot of firsts during that time. There are a few examples in chapters of The Arbornaut—instances that happen to me subsequently being the only woman in the room, which is still something that does happen. It’s what we call in Australia—my second home—the “tall poppy syndrome,” when women hit mid-career or senior status, and sometimes men resent that and like to cut them down a little bit. And I’m sure it’s in journalism, I’m sure it happens in Hollywood, in medicine and education. So I have a whole chapter just where I touch on these issues throughout my career that I hope are helpful to other women that are coming up the ladder behind me.

How did you spin that tumultuous time into something meaningful after you left?

I got invited to be the first professor of environmental studies at New College, which really allowed me to thrive because we set up a seminar series teaching students about board development, foundations and philanthropy. I had new energy, I was really excited to use my talents for the students in college. It was a really fun time. We did all sorts of programs out at the Myakka canopy walkway and the TREE Foundation funded a lot of that. We created some great partnerships with the county where all the students did internships. Many received awards from the county and got jobs from that. So it was a very positive channel. In the end, it was all good—sometimes change is good.

What is the biggest secret you feel you’ve uncovered studying the rain forests as deeply as you have?

For me, the biggest secret would be the discovery of the eighth continent getting into the tops of the trees. I was only planning to measure leaves and look at how long they lived, and then I found out that millions of critters were up there living in the treetops. And now that I know that, it makes sense—that’s where the sun is, that’s where the flowers are, that’s where all the energy is. But nobody really knew that because they didn’t climb a tree and they didn’t measure it. So finding that was huge. And then the other thing that’s been really, I guess, life-changing for me and maybe a little more technical is to find out how important leaves are to drive the health of the planet. We now know that trees store carbon, which is keeping us alive. We know that trees produce the most energy of anything, leaves cleanse water, leaves are the homes of 50 percent of the biodiversity on the planet. So we know all of these associated importance values for trees that we didn’t know before we went into the canopy, which translates to “We gotta save them.”

Are there secrets still left to be learned?

So out of that 50 percent of biodiversity living in the tops of trees on our planet, we estimate 90 percent is undiscovered. We’ve only discovered about 10 percent because it’s only been me and a handful of others that are true arbornauts to date, because the field is so new. So if every kid could climb a tree, there would be five or 10 species for each one to discover—it’s amazing what could be up there that we don’t know of yet, their importance, values. Which ones might be a medical cure for something, which one could be a pollinator of an important plant, which vine might create the fabric of the future or some kind of wonderful. Finding a strong fiber that we could use in some way that we haven’t even invented yet to have stronger roofs or buildings. So there’s a whole bunch of discovery left. Most of these forest canopies have not been explored. I’ve been taking Sarasota groups to this site in the Amazon for 25 years—that amounts to about 25 people each time. That’s over 2,000 people. We still find new things every time, and we’re going to the same canopy walkway, looking in the same 200 treetops. We still marvel at how much new and exciting adventure exists there every time we travel back. So now imagine multiplying that by a million. The Amazon is pretty huge and we’re just tackling a little teensy-weensy piece of it.

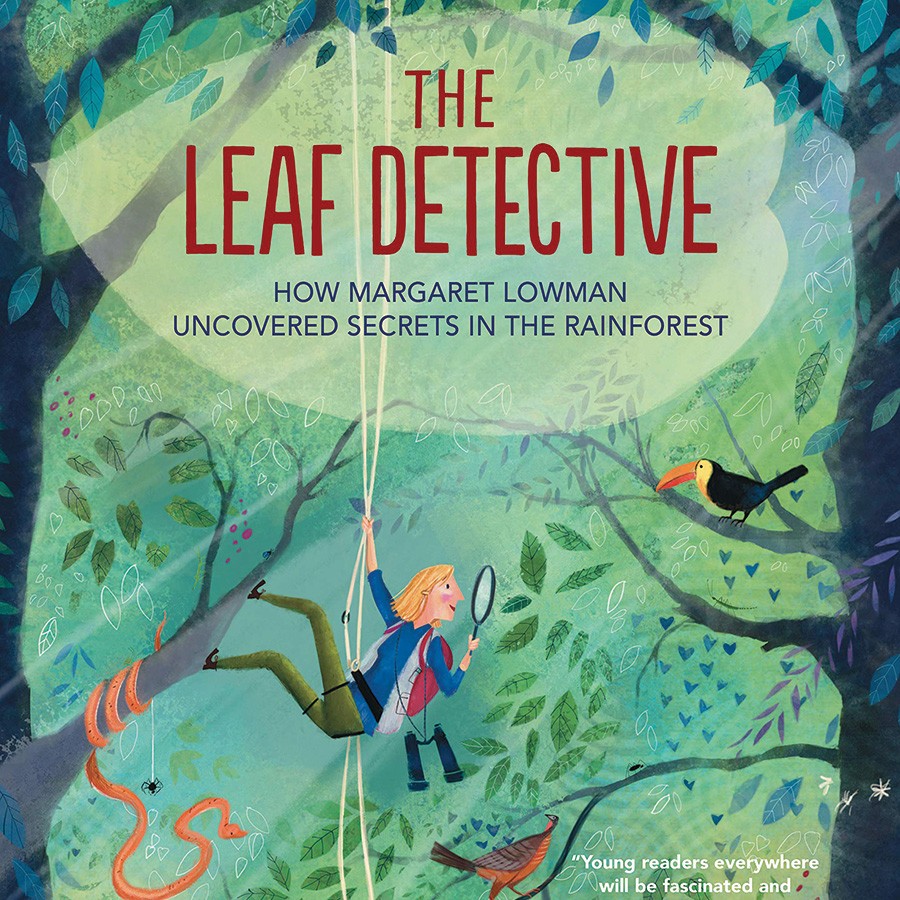

We love the cover of the children’s book, The Leaf Detective, written about you. It made us wonder what animals have surprised you, or that you have surprised, being up that high in the canopy?

Oh, all the time. And first of all, I can’t say enough good about bugs—good ol’ six-legged critters that we usually squish when they’re in our house—they are extraordinary. The colors and shapes in the canopy are beyond wonderful. Some bugs have a camouflage that look like a leaf that’s been eaten, the most gorgeous reds and chartreuse, psychedelic blue colors of beetles and almost all of them eat leaves, which fascinates me, personally, as a botanist. There’s a huge war going on up there: Insects eat leaves, leaves defend themselves with chemicals, the shamans use the chemicals for medicine. So there’s this amazing interaction of insects and leaves and medicines. The koala also eats exclusively leaves, as does the sloth. Leaves that are so full of toxins. These animals are basically on drugs all day hanging onto the branches. You think, “How on earth does their digestion really work?” The ultimate vegetarians. And then of course birds. I’m a bird lover from way back. I think I became a botanist because I really love birds and I didn’t want to lose my passion. The amazing hornbills in India with these giant big pieces of beak on their heads, it’s just beyond belief. And when you are dangling off a row, they’re not scared of you—you’re part of the scenery, so there’s no running away. You can get really close to troops of monkeys, lizards, I even patted a koala on its head because it’s right up there in the tree with me. It’s not about to bite me—it wants a leaf; it doesn’t want a finger.

What’s the farthest up off the ground that you’ve ever been? Have you ever been afraid of heights?

The farthest up I’d been was actually in a hot-air balloon—it’s a fabulous way of studying the very tippy tops of the trees, which are 300 to 350 feet in places like the redwoods in California and the tallest gums in Australia. Sometimes to get to the tops of these, you can’t use a rope for obvious reasons because you don’t have a strong enough branch. So that’s the highest I’ve been dangling from some of these inflatable things, which is truly fun; I’m sure it’s really dangerous, but it’s such a blast. But climbing on ropes, the tallest is probably about 200 feet. And yeah, I’m always a little afraid. I think probably a good arbornaut is someone who will always say there’s a little bit of tension and anxiety, because it is a safety sport. It’s like riding a mountain bike or something. You’ve got to have your wits about you and you’ve got to check your gear. So I have that little voice asking, “Is the branch strong enough?” “Is the rope OK?” “Has there been any alteration of my equipment?” So it’s always nice to come down, but it’s beautiful when I’m up there. I love it.

You do amazing work with young people—youth and children. Could you talk about the special connections children can have with their natural environment and why that is significant to you?

I guess my special passion is for more inclusivity in science. Partly because I was a kid that never had a role model, I never knew a scientist when I was a little girl. And I think it’s important for me to reach out to young people whenever I can. And I also think because I ended up as a tree climber for a living, there’s a connectivity with kids and climbing trees that maybe can help me inspire kids to love science. So I’ve done a lot with youth over the years, I was part of a project called the JASON project that used to broadcast out of Mote Marine Laboratory, which was started by Bob Ballard after he discovered the Titanic and kids wanted to take kids on expeditions, but you can’t obviously take a thousand kids on the water with you and you can’t take a thousand kids in the canopy with you.

In your Last Flight interview, you shared that when you were a kid, you dreamed of meeting a woman scientist. Look at you now! You are that woman scientist. What would you tell your younger self today about following those dreams—advice you would give her, things you might do differently, more or less of?

I would say two things, of which one would be, “Be bold.” I was such a shy kid—I’d never dare speak up. And I wished I’d been bolder and enabled my curiosity to have a bigger voice. So I would say to girls, try your best to be brave in that room full of boys and just speak up or be curious or be active. And then secondly, what I always say is, “Women support other women.” I think it’s one of the most important things we still need to do. And I get heartbroken when I see women that don’t behave that way, but you’ll see in the old-boy network men nominate men for prizes and help men negotiate. I think if women can help support women, we would be a lot further along in our ability to have confidence and be those role models that we want our girls to have.

What’s next for you and the TREE Foundation? What special projects are you working on at the moment?

One of my hopes is, now that I’ve moved back to Sarasota—I’m not in San Francisco or Raleigh or Singapore or all these other places like I usually am traveling to—I really do want to ramp up more local activities for kids in science. But I did start a whole new mission and it’s on the TREE Foundation website called Mission Green. We’re hoping this Mission Green will help us save a lot of the world’s species very quickly and very easily. Instead of saving trillions of hectares, we can focus on these special areas that scientists have already identified. I have an amazing dream team of science advisers and we’ve identified the 10 most important rain forests to save with the highest biodiversity—including Mozambique, Madagascar, even the great Smoky Mountains, the redwoods—where we need these ecotourism operations so that the local people can earn money by saving the trees and not logging the trees. So we plan to build canopy walkways. Myakka is the exemplar, a pillar model for the rest of the world, if you can believe it. We’ve applied for a local grant to ramp up the Myakka walkway because it’s the centerpiece on how walkways can educate kids and adults. We want to keep it vibrant and exciting. It gets half a million visitors a year, so if you add 20 years, times a half million, that means a lot of people have come through the Myakka River State Park and learned about its canopy walkway. We will be fundraising and building more of these walkways for conservation in tourism in places like Penang Island, Malaysia and Eureka, California. I’m soliciting for what I call “canopy angels.” People that would be initial donors and sit at the table with these famous scientists and be part of this team. And then we will build these walkways using local resources, and, hopefully, those guys from the World Treehouse Conference. SRQ